Neuroscience

Psychologists have known for some time that how we perceive the world is influenced by our physical capacity to act in it. For example, hills look steeper when you've got a heavy bag on your back. Objects seem nearer when you're holding a tool that allows you to reach further. Now Birte Moeller and her colleagues have extended this line of research to study how sitting in a stationary car affects people's perceptions of distance. Their findings, published recently in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, have real-life implications: for example, they could help explain why drivers often make misjudgments at traffic lights.

Psychologists have known for some time that how we perceive the world is influenced by our physical capacity to act in it. For example, hills look steeper when you've got a heavy bag on your back. Objects seem nearer when you're holding a tool that allows you to reach further. Now Birte Moeller and her colleagues have extended this line of research to study how sitting in a stationary car affects people's perceptions of distance. Their findings, published recently in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, have real-life implications: for example, they could help explain why drivers often make misjudgments at traffic lights.

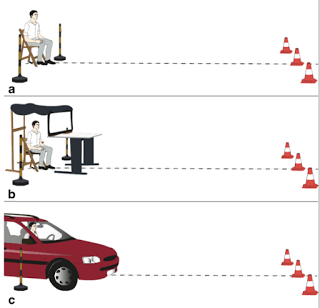

Forty-five participants (aged 19 to 54; 28 women) were allocated to judge distances in one of three conditions. Some of them sat in a Ford Escort, others sat on a chair, and a final group sat on a chair but behind a plastic screen that occluded their vision just the same as the Ford's windscreen. A traffic cone was placed at five different distances from the participants: 4 metres, 8 metres, 12 metres, 16 metres and 20 metres (roughly 13 feet to 65 feet), and a researcher stood by this cone holding two more cones. Each participant's task was to verbally direct the researcher to place his two cones horizontally the same distance from each other as the first target cone was distanced from the participant (thus creating a T-shape, with the participant at the foot of the T and the cones forming the horizontal roof of the T; see image).

All participants tended to underestimate the distances they were judging, which is a well-known phenomenon in perception research (that is, they tended to direct the researcher to place his cones too close together, indicating that they'd underestimated how far the first target cone was located from them).

However, the new and important finding was that the participants who were sitting in a car underestimated distances far more than the participants in the two comparison conditions. The participants in a car underestimated distances by around 40 per cent across all the different distances they were judging, whereas the other participants underestimated by between 15 and 30 per cent, with their underestimations being greater for larger distances.

Another detail was that participants in the car condition underestimated the distances even more when the estimation procedure was repeated after they'd spent a few minutes driving the car. By comparison, the tendency of the other participants to underestimate distances wasn't affected by spending the same time walking around.

Moeller and her colleagues think there could be two complementary reasons why sitting in a car affects people's judgment of distances: the first is that when we're in a car, our potential to act in the world is enhanced, which influences our perceptual system to make us think things are nearer; the second is that the car is effectively integrated into the "body schema" (our sense of where our body extends in space), much as hand-held tools are, so that distances are judged relative to the front of the car rather than to the self. Future research with different sized and powered cars could help disentangle these two effects.

This research has obvious real-life safety implications. While a driver's tendency to underestimate distances could be beneficial in some circumstances, for example by encouraging earlier braking, there are other contexts in which it could be dangerous, such as when judging how much time there is to pass through traffic lights that have turned amber. Also, the very fact that different road users – pedestrians, cyclists and drivers – likely have different perceptions of the same physical distances could help explain how some accidents occur.

"In sum," the researchers concluded, "entering a car does more to you than making transportation more comfortable. In fact, the moment you sit in your car, your (distance) perception of the environment seems to adapt to your new 'action potential,' again underlining how strongly related action and perception representations in the cognitive system are."

_________________________________

Moeller, B., Zoppke, H., & Frings, C. (2015). What a car does to your perception: Distance evaluations differ from within and outside of a car Psychonomic Bulletin & Review DOI: 10.3758/s13423-015-0954-9

Moeller, B., Zoppke, H., & Frings, C. (2015). What a car does to your perception: Distance evaluations differ from within and outside of a car Psychonomic Bulletin & Review DOI: 10.3758/s13423-015-0954-9

--further reading--

How tools become part of the body

Targets look bigger after a shot that felt good

Walking cane reveals dramatic sensory re-mapping by the brain

Judging others by our own capabilities

Welcome to the weird world of weight illusions

Post written by Christian Jarrett (@psych_writer) for the BPS Research Digest.

Our free fortnightly email will keep you up-to-date with all the psychology research we digest: Sign up!

- The Bigger You Get, The Harder It Is To Tell Whether You've Gained Or Lost Weight

When your waistband feels tighter than usual, or the scales say you've put on a few pounds, it's easy to blame the news on clothes shrinkage or an uneven carpet, especially if your body looks just the same in the mirror. And that lack of visual...

- The Woman With No Sense Of Personal Space

If I step aboard a crowded train and see that the only free space is a cramped mid-seat gap, sandwiched between two tired-looking commuters, then I will invariably choose to stand. By seizing the free spot, the unavoidable encroachment into my personal...

- Space Is Compressed By A Fast Turn Of Your Head

The raw immediacy of our waking lives leaves us feeling as though our five senses give us a true, undistorted perception of the world. But a catalogue of psychology experiments has shown this sense of experiencing the world "as it is" couldn't be...

- Encephalon 19 At Peripersonal Space

Encephalon 19: Emotion vs. Reason (a false dichotomy) and a hidden emotion quote embedded in the text appear at Peripersonal Space. Can you solve the mystery? Among the included posts are two from Neurophilosophy and (of course) The Phineas Gage Fan Club...

- Learning The Affordances For Maximum Distance Throwing

Over the last couple of posts, I have reviewed data that shows people can perceive which object they can, in fact, throw the farthest ahead of time by hefting the object. Both the size and the weight of the object affect people's judgements and the...

Neuroscience

When you're sitting in a car, things appear closer than they really are

Forty-five participants (aged 19 to 54; 28 women) were allocated to judge distances in one of three conditions. Some of them sat in a Ford Escort, others sat on a chair, and a final group sat on a chair but behind a plastic screen that occluded their vision just the same as the Ford's windscreen. A traffic cone was placed at five different distances from the participants: 4 metres, 8 metres, 12 metres, 16 metres and 20 metres (roughly 13 feet to 65 feet), and a researcher stood by this cone holding two more cones. Each participant's task was to verbally direct the researcher to place his two cones horizontally the same distance from each other as the first target cone was distanced from the participant (thus creating a T-shape, with the participant at the foot of the T and the cones forming the horizontal roof of the T; see image).

|

| Image from Moeller et al, 2015. |

However, the new and important finding was that the participants who were sitting in a car underestimated distances far more than the participants in the two comparison conditions. The participants in a car underestimated distances by around 40 per cent across all the different distances they were judging, whereas the other participants underestimated by between 15 and 30 per cent, with their underestimations being greater for larger distances.

Another detail was that participants in the car condition underestimated the distances even more when the estimation procedure was repeated after they'd spent a few minutes driving the car. By comparison, the tendency of the other participants to underestimate distances wasn't affected by spending the same time walking around.

Moeller and her colleagues think there could be two complementary reasons why sitting in a car affects people's judgment of distances: the first is that when we're in a car, our potential to act in the world is enhanced, which influences our perceptual system to make us think things are nearer; the second is that the car is effectively integrated into the "body schema" (our sense of where our body extends in space), much as hand-held tools are, so that distances are judged relative to the front of the car rather than to the self. Future research with different sized and powered cars could help disentangle these two effects.

This research has obvious real-life safety implications. While a driver's tendency to underestimate distances could be beneficial in some circumstances, for example by encouraging earlier braking, there are other contexts in which it could be dangerous, such as when judging how much time there is to pass through traffic lights that have turned amber. Also, the very fact that different road users – pedestrians, cyclists and drivers – likely have different perceptions of the same physical distances could help explain how some accidents occur.

"In sum," the researchers concluded, "entering a car does more to you than making transportation more comfortable. In fact, the moment you sit in your car, your (distance) perception of the environment seems to adapt to your new 'action potential,' again underlining how strongly related action and perception representations in the cognitive system are."

_________________________________

Moeller, B., Zoppke, H., & Frings, C. (2015). What a car does to your perception: Distance evaluations differ from within and outside of a car Psychonomic Bulletin & Review DOI: 10.3758/s13423-015-0954-9

Moeller, B., Zoppke, H., & Frings, C. (2015). What a car does to your perception: Distance evaluations differ from within and outside of a car Psychonomic Bulletin & Review DOI: 10.3758/s13423-015-0954-9 --further reading--

How tools become part of the body

Targets look bigger after a shot that felt good

Walking cane reveals dramatic sensory re-mapping by the brain

Judging others by our own capabilities

Welcome to the weird world of weight illusions

Post written by Christian Jarrett (@psych_writer) for the BPS Research Digest.

Our free fortnightly email will keep you up-to-date with all the psychology research we digest: Sign up!

- The Bigger You Get, The Harder It Is To Tell Whether You've Gained Or Lost Weight

When your waistband feels tighter than usual, or the scales say you've put on a few pounds, it's easy to blame the news on clothes shrinkage or an uneven carpet, especially if your body looks just the same in the mirror. And that lack of visual...

- The Woman With No Sense Of Personal Space

If I step aboard a crowded train and see that the only free space is a cramped mid-seat gap, sandwiched between two tired-looking commuters, then I will invariably choose to stand. By seizing the free spot, the unavoidable encroachment into my personal...

- Space Is Compressed By A Fast Turn Of Your Head

The raw immediacy of our waking lives leaves us feeling as though our five senses give us a true, undistorted perception of the world. But a catalogue of psychology experiments has shown this sense of experiencing the world "as it is" couldn't be...

- Encephalon 19 At Peripersonal Space

Encephalon 19: Emotion vs. Reason (a false dichotomy) and a hidden emotion quote embedded in the text appear at Peripersonal Space. Can you solve the mystery? Among the included posts are two from Neurophilosophy and (of course) The Phineas Gage Fan Club...

- Learning The Affordances For Maximum Distance Throwing

Over the last couple of posts, I have reviewed data that shows people can perceive which object they can, in fact, throw the farthest ahead of time by hefting the object. Both the size and the weight of the object affect people's judgements and the...