Neuroscience

The PYY and Dopamine Issue

The second study examined variations in the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter genes in 74 humans, fat and thin (Epstein et al., 2007). Obese individuals with the TaqI A1 allele were particularly susceptible to the reinforcing properties of food,

Footnote

1 Left orbitofrontal cortex, Midbrain PAG/VTA/SN, Right parabrachial nucleus, Right MSFG, Left MSFG, Right precentral gyrus, Middle frontal gyrus, Left posterior STG, Left posterior insula, Left anterior cingulate, Left inferior parietal lobule, Right lateral globus pallidus, right putamen, Right anterior lobe cerebellum, Left precentral gyrus (from Supplementary Table S1 of Batterham et al.).

References

Batterham RL, Ffytche DH, Rosenthal JM, Zelaya FO, Barker GJ, Withers DJ, Williams SC. (2007). PYY modulation of cortical and hypothalamic brain areas predicts feeding behaviour in humans. Nature Oct 14; [Epub ahead of print].

The ability to maintain adequate nutrient intake is critical for survival. Complex interrelated neuronal circuits have developed in the mammalian brain to regulate many aspects of feeding behaviour, from food-seeking to meal termination. The hypothalamus and brainstem are thought to be the principal homeostatic brain areas responsible for regulating body weight. However, in the current 'obesogenic' human environment food intake is largely determined by non-homeostatic factors including cognition, emotion and reward, which are primarily processed in corticolimbic and higher cortical brain regions. Although the pleasure of eating is modulated by satiety and food deprivation increases the reward value of food, there is currently no adequate neurobiological account of this interaction between homeostatic and higher centres in the regulation of food intake in humans. Here we show, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, that peptide YY(3-36) (PYY), a physiological gut-derived satiety signal, modulates neural activity within both corticolimbic and higher-cortical areas as well as homeostatic brain regions. Under conditions of high plasma PYY concentrations, mimicking the fed state, changes in neural activity within the caudolateral orbital frontal cortex predict feeding behaviour independently of meal-related sensory experiences. In contrast, in conditions of low levels of PYY, hypothalamic activation predicts food intake. Thus, the presence of a postprandial satiety factor switches food intake regulation from a homeostatic to a hedonic, corticolimbic area. Our studies give insights into the neural networks in humans that respond to a specific satiety signal to regulate food intake. An increased understanding of how such homeostatic and higher brain functions are integrated may pave the way for the development of new treatment strategies for obesity.

The ability to maintain adequate nutrient intake is critical for survival. Complex interrelated neuronal circuits have developed in the mammalian brain to regulate many aspects of feeding behaviour, from food-seeking to meal termination. The hypothalamus and brainstem are thought to be the principal homeostatic brain areas responsible for regulating body weight. However, in the current 'obesogenic' human environment food intake is largely determined by non-homeostatic factors including cognition, emotion and reward, which are primarily processed in corticolimbic and higher cortical brain regions. Although the pleasure of eating is modulated by satiety and food deprivation increases the reward value of food, there is currently no adequate neurobiological account of this interaction between homeostatic and higher centres in the regulation of food intake in humans. Here we show, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, that peptide YY(3-36) (PYY), a physiological gut-derived satiety signal, modulates neural activity within both corticolimbic and higher-cortical areas as well as homeostatic brain regions. Under conditions of high plasma PYY concentrations, mimicking the fed state, changes in neural activity within the caudolateral orbital frontal cortex predict feeding behaviour independently of meal-related sensory experiences. In contrast, in conditions of low levels of PYY, hypothalamic activation predicts food intake. Thus, the presence of a postprandial satiety factor switches food intake regulation from a homeostatic to a hedonic, corticolimbic area. Our studies give insights into the neural networks in humans that respond to a specific satiety signal to regulate food intake. An increased understanding of how such homeostatic and higher brain functions are integrated may pave the way for the development of new treatment strategies for obesity.

Epstein LH, Temple JL, Neaderhiser BJ, Salis RJ, Erbe RW, Leddy JJ. (2007). Food reinforcement, the dopamine D-sub-2 receptor genotype, and energy intake in obese and nonobese humans. Behav Neurosci. 121:877-86.

The authors measured food reinforcement, polymorphisms of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter (DAT1) genes, and laboratory energy intake in 29 obese and 45 nonobese humans 18-40 years old. Food reinforcement was greater in obese than in nonobese individuals, especially in obese individuals with the TaqI A1 allele. Energy intake was greater for individuals high in food reinforcement and greatest in those high in food reinforcement with the TaqI A1 allele. No effect of the DAT1 genotype was observed. These data show that individual differences in food reinforcement may be important for obesity and that the DRD-sub-2 genotype may interact with food reinforcement to influence energy intake.

The authors measured food reinforcement, polymorphisms of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter (DAT1) genes, and laboratory energy intake in 29 obese and 45 nonobese humans 18-40 years old. Food reinforcement was greater in obese than in nonobese individuals, especially in obese individuals with the TaqI A1 allele. Energy intake was greater for individuals high in food reinforcement and greatest in those high in food reinforcement with the TaqI A1 allele. No effect of the DAT1 genotype was observed. These data show that individual differences in food reinforcement may be important for obesity and that the DRD-sub-2 genotype may interact with food reinforcement to influence energy intake.

Tschop MH, Ravussin E. (2007). Peptide YY: Obesity’s Cause and Cure? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Sep 11; [Epub ahead of print]

Ueno H, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta M, Nakazato M. (2007). The role of PYY in feeding regulation. Regul Pept. Sep 18; [Epub ahead of print].

- How Hunger Affects Our Financial Risk Taking

The hungrier an animal becomes, the more risks it's prepared to take in the search for food. Now, for the first time, Mkael Symmonds and colleagues have shown that our animal instinct to maintain a balanced metabolic state influences our decision-making...

- Obesity Is Not Like Being "addicted To Food"

Credit: Image courtesy of Aalto University Is it possible to be “addicted” to food, much like an addiction to substances (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, opiates) or behaviors (gambling, shopping, Facebook)? An extensive and growing literature uses this terminology...

- D1 Receptor Knock-out Mice Say, "no Cocaine For Us!"

"However, we'll still take plenty of food and opioid agonists!" Unlike mice with the dopamine D2 receptor "knocked out," D1 receptor-deficient mice will no longer self-administer cocaine: Caine SB, Thomsen M, Gabriel KI, Berkowitz JS, Gold LH, Koob...

- I'm Not As Slim As That Mouse

The Agony of Genetically Disrupted Melanocortin Receptors (MC4R). A new study suggests that blocking MC4R function in the central nervous system of rodents produces obesity by altering lipid metabolism and promoting fat deposition (Nogueiras et al.,...

- Today's Disorder: Prader Willi Syndrome

According to the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (UK): Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) was first described in 1956 by Swiss doctors, Prof. A Prader, Dr A Labhart and Dr H Willi, who recognised the condition as having unique and clearly definable features....

Neuroscience

The Hunger:

The PYY and Dopamine Issue

In preparation for Halloween, two new treats provide potential ways to trick the nervous system into thinking the stomach is full (Batterham et al., 2007) or into reducing the reinforcing properties of highly palatable food (Epstein et al., 2007). In the first experiment, PYY or saline were administered in a double-blind crossover fashion and then fMRI and physiological measures were taken from 8 male participants. PYY, a peptide that belongs to the same family as neuropeptide Y (NPY), is secreted from cells in the intestinal mucosa within 15 min after eating (Ueno et al., 2007):Brain 'hunger pathways' pinpointed

12:05 15 October 2007

Anna Gosline

The brain circuitry that influences how much food a person will eat – whether they feel starving or full – has been revealed by a new imaging study. The results may help target new treatments against obesity, say researchers.

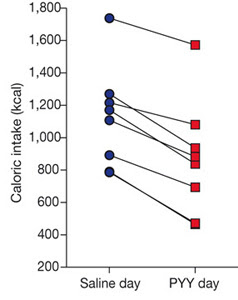

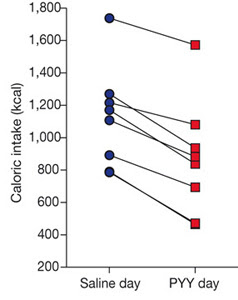

Rachel Batterham at University College London, UK, and her colleagues have previously shown that a hormone called peptide YY or PYY, which is released by the gut in proportion how many calories we eat, is a powerful appetite suppressant. Previous experiments show that treating normal and obese subjects with intravenous PYY decreases food intake by up to 30%.

Batterham's team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate how PYY affects the brain. They scanned each of eight subjects twice, once while they were on an intravenous drip of PYY, mimicking its release after a meal, and once while just receiving a saline solution. All the subjects had fasted for 14 hours prior to the scans.

Half an hour after they left the scanner, Batterham dished out an all-you-can-eat buffet of each subjects' favourite meals, which included spaghetti Bolognese and macaroni cheese.

As expected, those who received PYY ate less – on average 25% fewer calories. The fMRI scans showed that PYY not only lit up the hypothalamus – the main hub for controlling metabolism, – but also increased activity in higher processing areas of the brain that are associated with reward and pleasure, notably the orbital frontal cortex (OFC). "I absolutely wasn't expecting it to affect the reward circuit," says Batterham.

Via Y2 receptors, the satiety signal mediated by PYY inhibits NPY neurons and activates pro-opiomelanocortin neurons within the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Peripheral PYY(3-36) binds Y2 receptors on vagal afferent terminals to transmit the satiety signal to the brain. PYY(3-36) may have therapeutic potential in human obesity.PYY may even be a "silver bullet" and "obesity's cause and cure" according to some experts (Tschöp & Ravussin, 2007). Miracle cure or no, the fMRI data from subjects treated with PYY showed increases in a laundry list of brain areas1 , relative to saline (Batterham et al., 2007). The a priori regions of interest that covaried positively with PYY plasma concentrations were the hypothalamus, substantia nigra (chock-full of dopamine neurons), and parabrachial nucleus (taste relay center in the brainstem), but not the nucleus accumbens (hedonia central) or the nucleus of the solitary tract (another brainstem taste center). Of particular note in the whole-brain analysis was the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC):

Thus, in the presence of PYY, a postprandial satiety factor, brain activity predicting caloric intake appeared to switch from a homeostatic area (hypothalamus) to a hedonic area (OFC).Finally, the study participants treated with PYY ate 25% fewer calories at the all-you-can-eat buffet after the scanning session was over (see below, Fig. 1b of Batterham et al.)

The second study examined variations in the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter genes in 74 humans, fat and thin (Epstein et al., 2007). Obese individuals with the TaqI A1 allele were particularly susceptible to the reinforcing properties of food,

measured by determining the number of responses on a concurrent schedule task that participants made for food or food alternatives. The experimental environment included two computer stations with a swivel chair in the middle. At one station participants could earn points toward food, and at the other station they could earn points for time to spend reading the Buffalo News. [NOTE: because we all know how intrinsically rewarding this would be.] This alternative activity was provided to reduce the likelihood that participants would engage in responding out of boredom.The authors discuss the usefulness of these results in tailoring obesity treatment plans to the needs of individuals with lower intrinsic dopamine activity.

Dopamine levels and appetite

Science has found one likely contributor to the way that some folks eat to live and others live to eat.

Researchers at the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, have found that people with genetically lower dopamine, a neurotransmitter that helps make behaviors and substances more rewarding, find food to be more reinforcing than people without that genotype. In short, they are more motivated to eat and they eat more.

. . .

Epstein's team was particularly interested in the influence of the Taq1 A1 allele, a genetic variation linked to a lower number of dopamine D2 receptors and carried by about half the population (most of which carries one A1 and one A2; carriers of two A1 alleles are rare). The other half of the population carries two copies of A2, which by fostering more dopamine D2 receptors may make it easier to experience reward. People with fewer receptors need to consume more of a rewarding substance (such as drugs or food) to get that same effect.

. . .

Both obesity and the genotype associated with fewer dopamine D2 receptors predicted a significantly stronger response to food's reinforcing power. Perhaps not surprisingly, participants with that high level of food reinforcement consumed more calories.

The results also revealed a three-rung ladder of consumption, with people who don't find food that reinforcing, regardless of genotype, on the lowest rung. On the middle rung are people high in food reinforcement without the A1 allele. Atop the ladder are people high in food reinforcement with the allele, a potent combination that may put them at higher risk for obesity.

The reinforcing value of food, which may be influenced by dopamine genotypes, appeared to be a significantly stronger predictor of consumption than self-reported liking of the favorite food. What's more, obese participants clearly found food to be more reinforcing than non-obese participants. The authors conclude that, "Food is a powerful reinforcer that can be as reinforcing as drugs of abuse."

Editor's Note: Dr. Leonard Epstein is also a consultant to Kraft Foods.

Footnote

1 Left orbitofrontal cortex, Midbrain PAG/VTA/SN, Right parabrachial nucleus, Right MSFG, Left MSFG, Right precentral gyrus, Middle frontal gyrus, Left posterior STG, Left posterior insula, Left anterior cingulate, Left inferior parietal lobule, Right lateral globus pallidus, right putamen, Right anterior lobe cerebellum, Left precentral gyrus (from Supplementary Table S1 of Batterham et al.).

References

Batterham RL, Ffytche DH, Rosenthal JM, Zelaya FO, Barker GJ, Withers DJ, Williams SC. (2007). PYY modulation of cortical and hypothalamic brain areas predicts feeding behaviour in humans. Nature Oct 14; [Epub ahead of print].

The ability to maintain adequate nutrient intake is critical for survival. Complex interrelated neuronal circuits have developed in the mammalian brain to regulate many aspects of feeding behaviour, from food-seeking to meal termination. The hypothalamus and brainstem are thought to be the principal homeostatic brain areas responsible for regulating body weight. However, in the current 'obesogenic' human environment food intake is largely determined by non-homeostatic factors including cognition, emotion and reward, which are primarily processed in corticolimbic and higher cortical brain regions. Although the pleasure of eating is modulated by satiety and food deprivation increases the reward value of food, there is currently no adequate neurobiological account of this interaction between homeostatic and higher centres in the regulation of food intake in humans. Here we show, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, that peptide YY(3-36) (PYY), a physiological gut-derived satiety signal, modulates neural activity within both corticolimbic and higher-cortical areas as well as homeostatic brain regions. Under conditions of high plasma PYY concentrations, mimicking the fed state, changes in neural activity within the caudolateral orbital frontal cortex predict feeding behaviour independently of meal-related sensory experiences. In contrast, in conditions of low levels of PYY, hypothalamic activation predicts food intake. Thus, the presence of a postprandial satiety factor switches food intake regulation from a homeostatic to a hedonic, corticolimbic area. Our studies give insights into the neural networks in humans that respond to a specific satiety signal to regulate food intake. An increased understanding of how such homeostatic and higher brain functions are integrated may pave the way for the development of new treatment strategies for obesity.

The ability to maintain adequate nutrient intake is critical for survival. Complex interrelated neuronal circuits have developed in the mammalian brain to regulate many aspects of feeding behaviour, from food-seeking to meal termination. The hypothalamus and brainstem are thought to be the principal homeostatic brain areas responsible for regulating body weight. However, in the current 'obesogenic' human environment food intake is largely determined by non-homeostatic factors including cognition, emotion and reward, which are primarily processed in corticolimbic and higher cortical brain regions. Although the pleasure of eating is modulated by satiety and food deprivation increases the reward value of food, there is currently no adequate neurobiological account of this interaction between homeostatic and higher centres in the regulation of food intake in humans. Here we show, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, that peptide YY(3-36) (PYY), a physiological gut-derived satiety signal, modulates neural activity within both corticolimbic and higher-cortical areas as well as homeostatic brain regions. Under conditions of high plasma PYY concentrations, mimicking the fed state, changes in neural activity within the caudolateral orbital frontal cortex predict feeding behaviour independently of meal-related sensory experiences. In contrast, in conditions of low levels of PYY, hypothalamic activation predicts food intake. Thus, the presence of a postprandial satiety factor switches food intake regulation from a homeostatic to a hedonic, corticolimbic area. Our studies give insights into the neural networks in humans that respond to a specific satiety signal to regulate food intake. An increased understanding of how such homeostatic and higher brain functions are integrated may pave the way for the development of new treatment strategies for obesity.Epstein LH, Temple JL, Neaderhiser BJ, Salis RJ, Erbe RW, Leddy JJ. (2007). Food reinforcement, the dopamine D-sub-2 receptor genotype, and energy intake in obese and nonobese humans. Behav Neurosci. 121:877-86.

The authors measured food reinforcement, polymorphisms of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter (DAT1) genes, and laboratory energy intake in 29 obese and 45 nonobese humans 18-40 years old. Food reinforcement was greater in obese than in nonobese individuals, especially in obese individuals with the TaqI A1 allele. Energy intake was greater for individuals high in food reinforcement and greatest in those high in food reinforcement with the TaqI A1 allele. No effect of the DAT1 genotype was observed. These data show that individual differences in food reinforcement may be important for obesity and that the DRD-sub-2 genotype may interact with food reinforcement to influence energy intake.

The authors measured food reinforcement, polymorphisms of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter (DAT1) genes, and laboratory energy intake in 29 obese and 45 nonobese humans 18-40 years old. Food reinforcement was greater in obese than in nonobese individuals, especially in obese individuals with the TaqI A1 allele. Energy intake was greater for individuals high in food reinforcement and greatest in those high in food reinforcement with the TaqI A1 allele. No effect of the DAT1 genotype was observed. These data show that individual differences in food reinforcement may be important for obesity and that the DRD-sub-2 genotype may interact with food reinforcement to influence energy intake.Tschop MH, Ravussin E. (2007). Peptide YY: Obesity’s Cause and Cure? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Sep 11; [Epub ahead of print]

Ueno H, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta M, Nakazato M. (2007). The role of PYY in feeding regulation. Regul Pept. Sep 18; [Epub ahead of print].

- How Hunger Affects Our Financial Risk Taking

The hungrier an animal becomes, the more risks it's prepared to take in the search for food. Now, for the first time, Mkael Symmonds and colleagues have shown that our animal instinct to maintain a balanced metabolic state influences our decision-making...

- Obesity Is Not Like Being "addicted To Food"

Credit: Image courtesy of Aalto University Is it possible to be “addicted” to food, much like an addiction to substances (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, opiates) or behaviors (gambling, shopping, Facebook)? An extensive and growing literature uses this terminology...

- D1 Receptor Knock-out Mice Say, "no Cocaine For Us!"

"However, we'll still take plenty of food and opioid agonists!" Unlike mice with the dopamine D2 receptor "knocked out," D1 receptor-deficient mice will no longer self-administer cocaine: Caine SB, Thomsen M, Gabriel KI, Berkowitz JS, Gold LH, Koob...

- I'm Not As Slim As That Mouse

The Agony of Genetically Disrupted Melanocortin Receptors (MC4R). A new study suggests that blocking MC4R function in the central nervous system of rodents produces obesity by altering lipid metabolism and promoting fat deposition (Nogueiras et al.,...

- Today's Disorder: Prader Willi Syndrome

According to the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (UK): Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) was first described in 1956 by Swiss doctors, Prof. A Prader, Dr A Labhart and Dr H Willi, who recognised the condition as having unique and clearly definable features....