Neuroscience

We’re unaware of it, but starting in middle-age, our dominant hand gradually loses its superiority, so that we become, in a sense, more ambidextrous as we get older.

We’re unaware of it, but starting in middle-age, our dominant hand gradually loses its superiority, so that we become, in a sense, more ambidextrous as we get older.

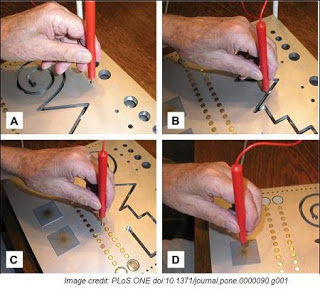

Tobias Kalisch and colleagues recruited 60 participants who were all strongly right-handed according to the commonly-used Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI), which asks people to indicate their favoured hand for several everyday activities. The participants then completed a range of computerised dexterity tests, including line tracing, an aiming task, and tapping (pictured left).

Consistent with their claims of right-handedness, the younger group of participants (average age 25 years) performed far better with their right hand on all the dexterity tests. By contrast, the middle-aged group (average age 50) performed just as well with either hand on the aiming task. And the two older groups (average age 70 and 80 years) performed just as well with either hand on all the tasks bar one.

Overall, performance tended to be poorer with increasing age, especially for the right hand. In other words, it seems we become more ambidextrous as we get older because our dominant hand loses its superior dexterity and becomes more like our weaker hand.

The findings were supported by a second experiment that used a gadget to record several hours of everyday hand use among 36 right-handed participants. The younger participants used their right hand far more than their left, whereas the older participants used both their hands a similar amount, despite claiming to be right-handed.

Neurophysiological studies don’t support the idea that one side of the brain ages more quickly than the other, so the researchers favour a “use-dependent plasticity” explanation for why our dominant hand loses its superiority. They said the dominance of our favoured hand is intensified through our use of it in everyday activities, so “when these activities decrease after retirement, or by the limitations in older age and sedentary lifestyles, it is conceivable that the practice-based superior performance of the right hand is no longer maintained…”.

__________________________________

Kalisch, T., Wilimzig, C., Kleibel, N., Tegenthoff, M. & Dinse, H.R. (2006). Age-related attenuation of dominant hand superiority. PLoS ONE, 1, 1-9. (Open access).

Post written by Christian Jarrett (@psych_writer) for the BPS Research Digest.

- Mirror Writing: What Does It Reflect About How We All Write?

Our story starts with a wheeze: a schoolboy punished with lines saves time by wielding two pens at once. Exploring the ease with which he can play with writing, what began as a diversion eventually becomes an artistic practice that incorporates mirrored...

- Performing Horizontal Eye Movement Exercises Can Boost Your Creativity

There have been prior clues that creativity benefits from ample cross-talk between the brain hemispheres. For example, patients who've had a commissurotomy - the severing of the thick bundle of nerve fibres that joins the two hemispheres - show deficits...

- Getting In Touch With Our Shadows

The sight of our own shadows can affect our sense of touch. That's according to Francesco Pavani and Giovanni Galfano who have shown that seeing the shadow of a part of your body automatically directs your tactile attention to that body part. Forty-two...

- An Ignoring Impairment

As part of the normal ageing process, some older people show an impairment in their ability to ignore information that is irrelevant to the task at hand, but their ability to enhance processing of relative stimuli remains intact. Adam Gazzaley (pictured)...

- Hemispheric Bias Shifts With Tiredness

Normally we have a slight bias to the left-hand side of space. So if we’re asked to mark the centre of a line, for example, we tend to overestimate the length of the left-hand portion. Now Tom Manly (pictured) at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences...

Neuroscience

We become more ambidextrous as we get older

Tobias Kalisch and colleagues recruited 60 participants who were all strongly right-handed according to the commonly-used Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI), which asks people to indicate their favoured hand for several everyday activities. The participants then completed a range of computerised dexterity tests, including line tracing, an aiming task, and tapping (pictured left).

Consistent with their claims of right-handedness, the younger group of participants (average age 25 years) performed far better with their right hand on all the dexterity tests. By contrast, the middle-aged group (average age 50) performed just as well with either hand on the aiming task. And the two older groups (average age 70 and 80 years) performed just as well with either hand on all the tasks bar one.

Overall, performance tended to be poorer with increasing age, especially for the right hand. In other words, it seems we become more ambidextrous as we get older because our dominant hand loses its superior dexterity and becomes more like our weaker hand.

The findings were supported by a second experiment that used a gadget to record several hours of everyday hand use among 36 right-handed participants. The younger participants used their right hand far more than their left, whereas the older participants used both their hands a similar amount, despite claiming to be right-handed.

Neurophysiological studies don’t support the idea that one side of the brain ages more quickly than the other, so the researchers favour a “use-dependent plasticity” explanation for why our dominant hand loses its superiority. They said the dominance of our favoured hand is intensified through our use of it in everyday activities, so “when these activities decrease after retirement, or by the limitations in older age and sedentary lifestyles, it is conceivable that the practice-based superior performance of the right hand is no longer maintained…”.

__________________________________

Kalisch, T., Wilimzig, C., Kleibel, N., Tegenthoff, M. & Dinse, H.R. (2006). Age-related attenuation of dominant hand superiority. PLoS ONE, 1, 1-9. (Open access).

Post written by Christian Jarrett (@psych_writer) for the BPS Research Digest.

- Mirror Writing: What Does It Reflect About How We All Write?

Our story starts with a wheeze: a schoolboy punished with lines saves time by wielding two pens at once. Exploring the ease with which he can play with writing, what began as a diversion eventually becomes an artistic practice that incorporates mirrored...

- Performing Horizontal Eye Movement Exercises Can Boost Your Creativity

There have been prior clues that creativity benefits from ample cross-talk between the brain hemispheres. For example, patients who've had a commissurotomy - the severing of the thick bundle of nerve fibres that joins the two hemispheres - show deficits...

- Getting In Touch With Our Shadows

The sight of our own shadows can affect our sense of touch. That's according to Francesco Pavani and Giovanni Galfano who have shown that seeing the shadow of a part of your body automatically directs your tactile attention to that body part. Forty-two...

- An Ignoring Impairment

As part of the normal ageing process, some older people show an impairment in their ability to ignore information that is irrelevant to the task at hand, but their ability to enhance processing of relative stimuli remains intact. Adam Gazzaley (pictured)...

- Hemispheric Bias Shifts With Tiredness

Normally we have a slight bias to the left-hand side of space. So if we’re asked to mark the centre of a line, for example, we tend to overestimate the length of the left-hand portion. Now Tom Manly (pictured) at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences...