Neuroscience

With a deft mix of brain imaging and memory testing, researchers in Sweden believe they've identified neural activity that is responsible for controlling what information is allowed into our working memory - the mental store we use over brief periods, such as when dialling a phone number.

With a deft mix of brain imaging and memory testing, researchers in Sweden believe they've identified neural activity that is responsible for controlling what information is allowed into our working memory - the mental store we use over brief periods, such as when dialling a phone number.

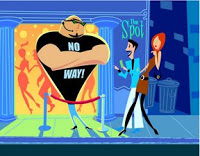

This activity, which was observed in the globus pallidus (part of a larger cluster of subcortical cells called the basal ganglia) acts as a kind of bouncer to working memory, keeping out the irrelevant riff raff.

Twenty-five female participants had their brains scanned while they memorised the location of squares and/or circles in a circular grid. An instruction before each trial informed them whether the circles, if present, were on the guest list - that is, whether they should be remembered or ignored.

Brain activity observed during these instructions increased in parts of the prefrontal cortex and the globus pallidus - reflecting the metaphorical bouncer readying himself for action.

The amount of filtering activity shown by the bouncer (in this case, in the globus pallidus, but not the prefrontal cortex) was related to how much memory-related activity was observed near the crown of the head, in the parietal cortex, when the participants were presented with a mix of squares to be remembered and circles to be ignored. That is, participants who showed less bouncer-type activity subsequently showed more memory-store activity when to-be-ignored circles were present. This makes perfect sense because it suggests more irrelevant material had been allowed into their working memory.

Of course, storing irrelevant material is inefficient and in a separate memory test, outside of the brain scanner, the participants with the more active 'memory bouncers' were found to have more working memory capacity.

"The present results therefore reveal a specific neural mechanism by which an individual's ability to exert control over the encoding of new information is linked to their working memory capacity," Fiona McNab and colleagues concluded.

_________________________________

McNab, F. & Klingberg, T. (2007). Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia control access to working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 103-107.

Post written by Christian Jarrett (@psych_writer) for the BPS Research Digest.

- Students: It's Time To Ditch The Pre-exam All-nighter

Lack of sleep impairs the human brain's ability to store new information in memory, researchers have found. Past research has already shown that sleep is vital for consolidating recently-learned material but now Matthew Walker and colleagues have...

- Fusing Psychology And Neuroscience

By Chris Chatham, of Developing Intelligence. Psychology is appealing to me partly because it requires so much stealthiness. We can't directly observe mental events, but must instead use indirect methods to test our hypotheses. We must cleverly misdirect...

- You Won't Forget This

Last year researchers reported they were able to use real-time images of a person’s brain activity to tell what version of an ambiguous shape they were looking at. Now Leun Otten and colleagues report that they can use measures of the brain’s surface...

- An Ignoring Impairment

As part of the normal ageing process, some older people show an impairment in their ability to ignore information that is irrelevant to the task at hand, but their ability to enhance processing of relative stimuli remains intact. Adam Gazzaley (pictured)...

- I Should've Forgotten That

from Feredoes et al. (2006) The illustration above is from a brand new paper by Feredoes, Tononi, and Postle that used the latest in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) technology to transiently disrupt bits of cortex (targeted regions indicated...

Neuroscience

Introducing the brain's memory bouncer

With a deft mix of brain imaging and memory testing, researchers in Sweden believe they've identified neural activity that is responsible for controlling what information is allowed into our working memory - the mental store we use over brief periods, such as when dialling a phone number.

With a deft mix of brain imaging and memory testing, researchers in Sweden believe they've identified neural activity that is responsible for controlling what information is allowed into our working memory - the mental store we use over brief periods, such as when dialling a phone number.This activity, which was observed in the globus pallidus (part of a larger cluster of subcortical cells called the basal ganglia) acts as a kind of bouncer to working memory, keeping out the irrelevant riff raff.

Twenty-five female participants had their brains scanned while they memorised the location of squares and/or circles in a circular grid. An instruction before each trial informed them whether the circles, if present, were on the guest list - that is, whether they should be remembered or ignored.

Brain activity observed during these instructions increased in parts of the prefrontal cortex and the globus pallidus - reflecting the metaphorical bouncer readying himself for action.

The amount of filtering activity shown by the bouncer (in this case, in the globus pallidus, but not the prefrontal cortex) was related to how much memory-related activity was observed near the crown of the head, in the parietal cortex, when the participants were presented with a mix of squares to be remembered and circles to be ignored. That is, participants who showed less bouncer-type activity subsequently showed more memory-store activity when to-be-ignored circles were present. This makes perfect sense because it suggests more irrelevant material had been allowed into their working memory.

Of course, storing irrelevant material is inefficient and in a separate memory test, outside of the brain scanner, the participants with the more active 'memory bouncers' were found to have more working memory capacity.

"The present results therefore reveal a specific neural mechanism by which an individual's ability to exert control over the encoding of new information is linked to their working memory capacity," Fiona McNab and colleagues concluded.

_________________________________

McNab, F. & Klingberg, T. (2007). Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia control access to working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 103-107.

Post written by Christian Jarrett (@psych_writer) for the BPS Research Digest.

- Students: It's Time To Ditch The Pre-exam All-nighter

Lack of sleep impairs the human brain's ability to store new information in memory, researchers have found. Past research has already shown that sleep is vital for consolidating recently-learned material but now Matthew Walker and colleagues have...

- Fusing Psychology And Neuroscience

By Chris Chatham, of Developing Intelligence. Psychology is appealing to me partly because it requires so much stealthiness. We can't directly observe mental events, but must instead use indirect methods to test our hypotheses. We must cleverly misdirect...

- You Won't Forget This

Last year researchers reported they were able to use real-time images of a person’s brain activity to tell what version of an ambiguous shape they were looking at. Now Leun Otten and colleagues report that they can use measures of the brain’s surface...

- An Ignoring Impairment

As part of the normal ageing process, some older people show an impairment in their ability to ignore information that is irrelevant to the task at hand, but their ability to enhance processing of relative stimuli remains intact. Adam Gazzaley (pictured)...

- I Should've Forgotten That

from Feredoes et al. (2006) The illustration above is from a brand new paper by Feredoes, Tononi, and Postle that used the latest in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) technology to transiently disrupt bits of cortex (targeted regions indicated...