Neuroscience

Fig. 1. (A) Experimental procedure [adapted from Depue et al., 2007]. Individuals were first trained to associate 40 cue faces with 40 nasty target pictures. During the fMRI phase, individuals viewed only faces. On some trials they were instructed to think of the previously learned picture; on other trials they were instructed not to let the previously associated picture enter consciousness [no-think]. The presentation of only the cue (i.e., the face) ensures that individuals manipulate the memory of the target picture. Additional faces not shown during this phase acted as a behavioral baseline. During the test phase, participants were shown the 40 faces and asked to describe the previously associated picture.

Can you selectively and willfully forget (or at least, suppress) the past, particularly the most negative events? Not with a drug or ECT, but by using your brain's intrinsic "executive control"1 abilities? As mentioned the other day in I Forget, the promise of propranolol has been overhyped. But can PTSD patients (and others with traumatic memories) be trained to forget their waking nightmares? Can one harness the intrinsic plasticity of the brain to "unlearn" (rather than learn)? As Dr. Michael Merzenich wrote recently:

Further details on the procedure were contained in the Supporting Online Material:

Further details on the procedure were contained in the Supporting Online Material:

What were the brain imaging results? First, let's look at the data from the 2004 experiment of Anderson et al., which used word pairs as stimuli (e.g., roach-ordeal, steam-train, jaw-gum) instead of face-picture pairs.

Fig. 2 (Anderson et al., 2004). Activation for Suppression trials compared with Respond trials during the think/no-think phase. Areas in yellow were more active during Suppression trials than during Respond trials, whereas areas in blue were less active during Suppression (P less than 0.001, uncorrected). White arrows highlight hippocampal deactivation in the Suppression condition.

Fig. 2 (Anderson et al., 2004). Activation for Suppression trials compared with Respond trials during the think/no-think phase. Areas in yellow were more active during Suppression trials than during Respond trials, whereas areas in blue were less active during Suppression (P less than 0.001, uncorrected). White arrows highlight hippocampal deactivation in the Suppression condition.

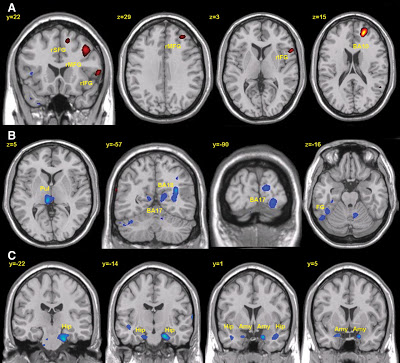

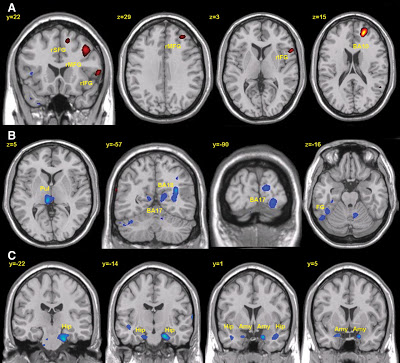

Fig. 2 (Depue et al., 2007). Functional activation of brain areas involved in (A) cognitive control, (B) sensory representations of memory, and (C) memory processes and emotional components of memory. ... Red indicates greater activity for NT trials than for T trials; blue indicates the reverse. Conjunction analyses revealed that areas seen in blue are the culmination of increased activity for T trials above baseline as well as decreased activity of NT trials below baseline.

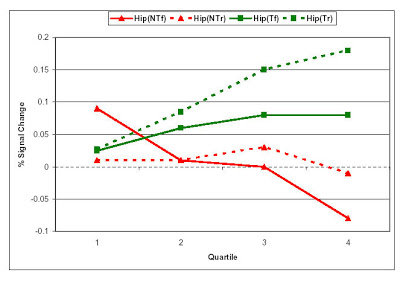

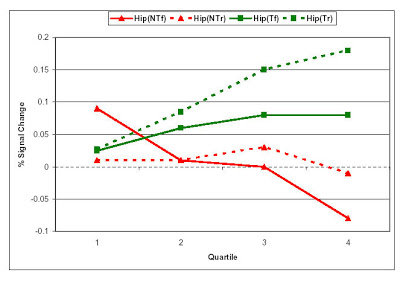

Finally, the authors divided the data up into quartiles based on the order of experiment trials -- i.e., Q1 was comprised of trials 1-3, Q2 was 4-6, etc. to reveal the two phases of memory suppression:

Fig S3 (Depue et al., 2007). Percent signal change analysis in the hippocampus over all quartiles for NT trials that were forgotten (NTf, red solid line), NT trials that were remembered (NTr, red dashed line), T trials that were forgotten (Tf, green dashed line), and T trials that were remembered (Tr, green solid line).

So do these findings have any relevance for suppressing traumatic memories in PTSD? Opinions are mixed:

1 Or as it is more fashionably called these days, "cognitive control."

References

Anderson MC, Green C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control. Nature 410:131-134.

Anderson, M.C., Ochsner, K.N., Kuhl, B., Cooper, J., Robertson, E., Gabrieli, S.W., Glover, G.H., Gabrieli, J.D.E. (2004). Neural systems underlying the suppression of unwanted memories. Science 303:232-235.

Depue BE, Curran T, Banich MT. (2007). Prefrontal Regions Orchestrate Suppression of Emotional Memories via a Two-Phase Process. Science 317:215-219.

- Repression Debunked

Psychologists in Denmark have hammered another nail into the coffin containing 'repression' - the idea, made popular by psychoanalysis, that negative, emotional memories are particularly prone to be being locked up out of conscious reach. Simon...

- Remembering And Forgetting In Traumatized Ugandan Refugees

Gulu, Uganda (vis photography) Most of us have memories from the past that we'd rather forget. When those memories are of a traumatic nature, they can more difficult to expel from our minds. Unwanted memories can be rejected by means of active inhibitory...

- Living And Forgetting

And I'll be easy Like living and forgetting And if I pick you up I'll be sure to let you down -Living and Forgetting, Glasstown (mp3) Forgetting Emotional Information Is Hard Our memory for emotional events is generally better than our memory...

- I Forget...

Forgotten, by Linkin Park From the top to the bottom Bottom to top I stop At the core I’ve forgotten In the middle of my thoughts Taken far from my safety The picture is there The memory won't escape me But why should I care Chester Bennington...

- Daydreaming And Thought-sampling

OK, is there anything new in the daydreaming article in Science? Fig. 2. Graphs depict regions that exhibited a significant positive relation [with a propensity to daydream], r(14) > 0.50, P < .05 (A) Bilateral mPFC; (B) Bilateral precuneus and posterior...

Neuroscience

I Forgot...

Fig. 1. (A) Experimental procedure [adapted from Depue et al., 2007]. Individuals were first trained to associate 40 cue faces with 40 nasty target pictures. During the fMRI phase, individuals viewed only faces. On some trials they were instructed to think of the previously learned picture; on other trials they were instructed not to let the previously associated picture enter consciousness [no-think]. The presentation of only the cue (i.e., the face) ensures that individuals manipulate the memory of the target picture. Additional faces not shown during this phase acted as a behavioral baseline. During the test phase, participants were shown the 40 faces and asked to describe the previously associated picture.

Can you selectively and willfully forget (or at least, suppress) the past, particularly the most negative events? Not with a drug or ECT, but by using your brain's intrinsic "executive control"1 abilities? As mentioned the other day in I Forget, the promise of propranolol has been overhyped. But can PTSD patients (and others with traumatic memories) be trained to forget their waking nightmares? Can one harness the intrinsic plasticity of the brain to "unlearn" (rather than learn)? As Dr. Michael Merzenich wrote recently:

BRAIN PLASTICITY IS A TWO-WAY STREET. It is “negative” plasticity that generates the changes in the brain that underly the impaired operational state of the depressed or stressed or anxious or obsessed or traumatized individual. PTSD, for example, is a PRODUCT of brain plasticity. Just as I can plausibly create a positive brain plasticity-based approach to re-normalize the brain of the PTSD patient, so, too, can I create the malady itself, at will, by training the brain in ways that drive specific “negative” changes within it.These questions were not answered by a brand new fMRI paper in Science (Depue et al., 2007), but a more modest goal was to determine whether the neural activity (or rather, the hemodynamic response) in certain brain regions dipped below baseline levels when participants were actively trying to suppress thinking about unpleasant pictures (see above) that were paired with neutral faces. The study adapted the "think/no-think" paradigm of Dr. Michael C. Anderson (et al., 2001, 2004), who heads the Memory Control Lab at the University of Oregon.

Further details on the procedure were contained in the Supporting Online Material:

Further details on the procedure were contained in the Supporting Online Material:Similar to Anderson and Green, in the Think condition, participants were told "Think of the picture previously associated with the face", whereas in the No-Think condition they were told "Do not to let the previously associated picture come into consciousness." Within each condition (Think/No-Think), participants viewed the faces 12 times. The 8 faces not shown in the experimental phase served as a zero-repetition behavioral baseline.The behavioral manipulation was effective in suppressing memory: mean recall rates were 71.1% in the think condition, compared to 53.3% in the no-think condition. Baseline recall was 62.5% (when subjects viewed the face-picture pair only in the training phase, but did not get 12 presentations of the face only in the experimental phase).

What were the brain imaging results? First, let's look at the data from the 2004 experiment of Anderson et al., which used word pairs as stimuli (e.g., roach-ordeal, steam-train, jaw-gum) instead of face-picture pairs.

Fig. 2 (Anderson et al., 2004). Activation for Suppression trials compared with Respond trials during the think/no-think phase. Areas in yellow were more active during Suppression trials than during Respond trials, whereas areas in blue were less active during Suppression (P less than 0.001, uncorrected). White arrows highlight hippocampal deactivation in the Suppression condition.

Fig. 2 (Anderson et al., 2004). Activation for Suppression trials compared with Respond trials during the think/no-think phase. Areas in yellow were more active during Suppression trials than during Respond trials, whereas areas in blue were less active during Suppression (P less than 0.001, uncorrected). White arrows highlight hippocampal deactivation in the Suppression condition.A network of brain regions was more active during suppression than during retrieval, including bilateral dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC and VLPFC, respectively; Brodmann's area (BA) 45/46, stronger on left); anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; BA 32); the contiguous pre-supplementary motor area (preSMA; BA 6), a lateral premotor area in the rostral portion of the dorsal premotor cortex (PMDr; BA 6/9); and the intraparietal sulcus (IPS; BA 7) (also in bilateral BA 47/BA 13, and right putamen).Furthermore, the degree of activity in bilateral DLPFC and left VLPFC [and a few other places] was related to an individual's ability to suppress remembering in the no-think condition (Anderson et al., 2004). So were the results similar in the current study, or did they differ due to the use of yucky pictures (from the IAPS) as the suppressed stimuli?

Prefrontal regions, right-sided and spanning BA 8, 9/46, 47, and BA 10, exhibited NT > T contrast. A conjunction analysis indicated that these differences resulted from an increase in activity for NT trials rather than a decrease in activation for T trials relative to baseline (Fig. 2A), which suggests that these regions are specifically involved in controlling the suppression of emotional memories.

Brain areas underlying the sensory representation of memory that showed such an effect [NT greater than T, NT negative relative to baseline, and T positive relative to baseline] were the visual cortex, including bilateral BA17, BA18, and BA37 [fusiform gyrus (FG)], and the pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus (Pul; Fig. 2B). Suppression of emotional memories thus involved decreased activity in sensory cortices that are normally active when memories are being retrieved, as well as in regions (i.e., Pul) that play a role in gating and modulating attention toward or away from visual stimuli.And the hippocampus and amygdala showed no-think reductions in activity (Fig 2C), as would be expected for structures involved in memory and emotion, respectively.

Finally, the authors divided the data up into quartiles based on the order of experiment trials -- i.e., Q1 was comprised of trials 1-3, Q2 was 4-6, etc. to reveal the two phases of memory suppression:

Two patterns of temporal change in activation were observed, each associated with different groupings of prefrontal and posterior brain areas. The two groupings were composed of (i) right inferior frontal gyrus (rIFG), Pul, and FG, and (ii) right middle frontal gyrus (rMFG), Hip, and Amy [Hip and Amy! love the abbreviations!] ... rIFG showed early activation in the time course of suppression, which lasted through the second quartile of repetitions... Greater activity in rIFG in the second quartile was significantly associated with decreased activity in Pul and FG during the second quartile...But who's controlling these controllers? Why, Brodmann area 10 (frontopolar cortex) is the orchestra's conductor! And that's not all! It seems to me that the hippocampus showed a wacky pattern of activity.

In contrast to rIFG, rMFG activation increased later and remained active. Activity in Hip and Amy appeared to follow that of rMFG in reverse... Increased activity in rMFG did not predict activity in Hip and Amy in the first or second quartiles, but did so significantly in the third and fourth quartiles.

Fig S3 (Depue et al., 2007). Percent signal change analysis in the hippocampus over all quartiles for NT trials that were forgotten (NTf, red solid line), NT trials that were remembered (NTr, red dashed line), T trials that were forgotten (Tf, green dashed line), and T trials that were remembered (Tr, green solid line).

So do these findings have any relevance for suppressing traumatic memories in PTSD? Opinions are mixed:

Rather not remember? You can fuggedabouditFootnote

by Kavita Mishra

. . .

New research suggests that people can push out memories, even highly emotional ones, simply by deciding to do so.

The researchers believe the new findings will help scientists understand disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, in which the brain's mechanism of suppressing unwanted memories may be dysfunctional, said lead author Brendan Depue, a graduate student in neuroscience and clinical psychology at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

But many experts are wary of linking the findings -- published today in the online journal Science -- to debilitating disorders like PTSD. They believe the mind developed to actively forget some memories to keep from cluttering the brain with unpleasant memories and irrelevant information, like unnecessary phone numbers. But highly emotional memories may never be forgotten.

"We have these mechanisms to try to stamp out and suppress these things when we want to try to avoid uncomfortable thoughts. On the other hand, we do know that very serious emotional memories are, in general, very remembered," UC Berkeley psychologist Art Shimamura said.

. . .

Dr. Thomas Neylan, a PTSD expert at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, said training in memory suppression is not the goal of treatment in many disorders. "Effective treatment (in PTSD) is to promote a new form of learning," he said. "When a person retrieves the memory of the trauma, they no longer associate it with all the same feelings of fear and arousal. With repetition, they are no longer as aroused, upset or angry. That process involves a new form of learning, not memory suppression."

1 Or as it is more fashionably called these days, "cognitive control."

References

Anderson MC, Green C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control. Nature 410:131-134.

Anderson, M.C., Ochsner, K.N., Kuhl, B., Cooper, J., Robertson, E., Gabrieli, S.W., Glover, G.H., Gabrieli, J.D.E. (2004). Neural systems underlying the suppression of unwanted memories. Science 303:232-235.

Depue BE, Curran T, Banich MT. (2007). Prefrontal Regions Orchestrate Suppression of Emotional Memories via a Two-Phase Process. Science 317:215-219.

- Repression Debunked

Psychologists in Denmark have hammered another nail into the coffin containing 'repression' - the idea, made popular by psychoanalysis, that negative, emotional memories are particularly prone to be being locked up out of conscious reach. Simon...

- Remembering And Forgetting In Traumatized Ugandan Refugees

Gulu, Uganda (vis photography) Most of us have memories from the past that we'd rather forget. When those memories are of a traumatic nature, they can more difficult to expel from our minds. Unwanted memories can be rejected by means of active inhibitory...

- Living And Forgetting

And I'll be easy Like living and forgetting And if I pick you up I'll be sure to let you down -Living and Forgetting, Glasstown (mp3) Forgetting Emotional Information Is Hard Our memory for emotional events is generally better than our memory...

- I Forget...

Forgotten, by Linkin Park From the top to the bottom Bottom to top I stop At the core I’ve forgotten In the middle of my thoughts Taken far from my safety The picture is there The memory won't escape me But why should I care Chester Bennington...

- Daydreaming And Thought-sampling

OK, is there anything new in the daydreaming article in Science? Fig. 2. Graphs depict regions that exhibited a significant positive relation [with a propensity to daydream], r(14) > 0.50, P < .05 (A) Bilateral mPFC; (B) Bilateral precuneus and posterior...