Neuroscience

** This post is meant to be read in tandem with its more complimentary cousin, Electroconvulsive Therapy Impairs Memory Reconsolidation, at The Neurocomplimenter. **

Bad memories haunt a significant number of people with serious mental illnesses, such as chronic major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). If it were possible to undergo an experimental procedure that selectively impairs your memory for an extremely unpleasant event, would you do it? If this sounds like the plot of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, you're not alone.

A pet peeve of mine is reference to this excellent but far-fetched film in scientific journals and popular media coverage of “memory erasure.” The idea that it's possible to selectively remove a complex autobiographical memory that has become intimately entwined with the fabric of our constructed selves is utter science fiction.

At some level, even Michel Gondry knew it. One incident in Eternal Sunshine is suggestive of how memories might actually be stored. It was after one of the main characters (Joel) had his memories of his ex-girlfriend Clementine erased, and he couldn't remember who Huckleberry Hound was. He had associated the cartoon character and the song "Darling Clementine" with her. That resembles a semantic network, where an overlapping network of neurons and synapses code different but semantically related things. Take out all episodic and semantic memories of Clementine, and knowledge of Huckleberry Hound goes with it.

The latest incarnation of this particular memory erasure meme was provoked by publication of a paper (Kroes et al., 2013) that examined the process of memory reconsolidation in depressed patients administered a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Here are some of the headlines:

My companion post at The Neurocomplimenter reviews the literature on memory reconsolidation and describes the experiment of Kroes et al. (2013) in some detail. What I'd like to do here is to point out possible weaknesses in the results that could undermine the authors' conclusions. I'll also discuss a much earlier ECT study which did not support the notion that reactivated memories are especially vulnerable to disruption (Squire et al., 1976).

To briefly reiterate the methods used in the new paper (Kroes et al., 2013), the participants were 39 patients with moderate to severe major depression. They were either at the end of an acute treatment cycle or receiving maintenance ECT. The study used a between-subjects design with three different experimental conditions, with patients randomly assigned to one of the three groups (n=13 in each). The within-subjects factor was whether or not the patients received a reminder of previously learned material before treatment.

All participants learned two different emotionally charged slide stories with audio narration, each consisting of 11 images. In one, a boy is in an accident that severs his feet, which are reattached at the hospital. In the other, two sisters leave their home at night, and one is kidnapped at knife point and attacked by an escaped convict.

Memory for one of the stories was reactivated a week later by presenting part of the first slide, and then giving a test for this slide. Only four minutes later, Groups A and B were anesthetized and received ECT. Group C received their ECT treatment at a later date. The final memory test for Groups A and C was 24 hrs after the reminder, while Group B was tested as soon as they woke up from the procedure (mean = 104 min later). The final test consisted of 40 multiple choice questions about each of the stories.

The basic idea is that reconsolidation of the reactivated story isn't complete within 104 min, so Group B's test performance should be the same for the two stories. In contrast, reconsolidation is complete by 24 hrs, so for Group A the disruptive effect of ECT should selectively impair memory for the transiently reactivated story, which is in a labile state (relative to the "consolidated" story learned 7 days earlier).

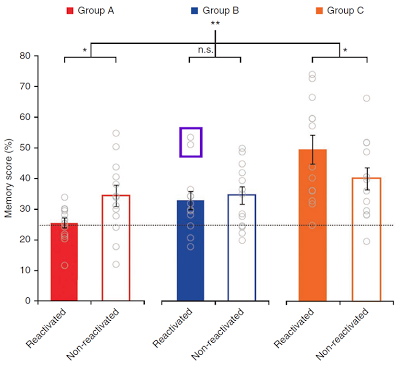

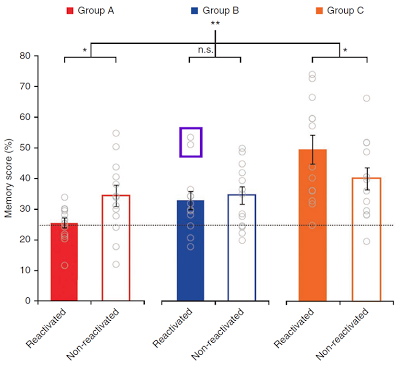

Is that what was observed? Statistically speaking, yes. But two patients in Group B (out of 13 total) performed very well on the reactivated story (see purple box in the figure below).

Fig. 1 (modified from Kroes et al. 2013). ECT disrupts reconsolidation. Memory scores on the multiple choice test are expressed as percentage correct (y axis). Memory for the reactivated story shown in solid bars and non-reactivated story in open bars. Each circle is the score for an individual patient. The horizontal dotted line is chance performance. Group A is in red, Group B in blue, and Group C in orange. Edited to add: The purple box highlights 2 outliers in Group B who could be driving the major effect.

If these two individuals are omitted, would the difference between Groups A and B still be significant? This is the key finding of the paper, that memory for the reactivated story is no better than chance if ECT disrupts reconsolidation (a time-dependent process). Hence all the Eternal Sunshine / “memory erasure” headlines.

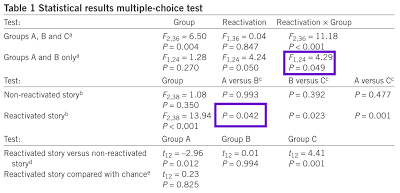

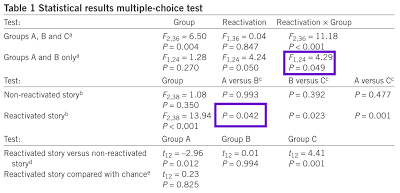

The purple boxes show that (1) the Reactivation x Group interaction squeaks in at just barely significant (p=.049); and (2) the Group A vs. Group B comparison for the reactivated story is p=.042. Clearly, it would be nice to include twice as many patients in each group. But it took the authors 3.5 years to recruit their final total of n=39.

This type of study is not easy to pull off, which is why I applaud the authors (and the patients) for such an ambitious undertaking. I thought it was a very clever idea as well, but not an original one as it turns out.

In the 1970s and 80s, Dr. Larry Squire and his colleagues published a series of papers on ECT and memory. The one I'll describe here takes a similar approach to Kroes et al. by testing previously learned material after ECT, and by giving a memory reminder just before the treatment (Squire et al., 1976).

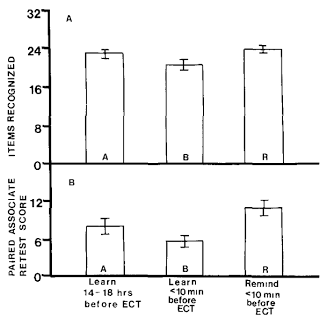

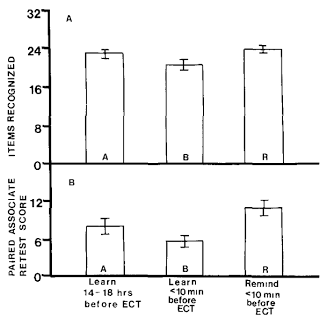

Squire et al. (1976) used a completely within-subjects design (n=12) that manipulated the pre-ECT learning interval (14-18 hrs vs. 3-10 min). The third condition presented a memory reminder 3-10 min before ECT for material learned 14-18 hrs previously. Completely different stimuli were used each time, and the order of conditions was counterbalanced. The memory tests were recognition memory for a set of 32 previously learned items (common objects, common words, yearbook photos, and nonsense drawings), and paired associates (producing the correct target for 18 previously learned cue-target pairs). In all conditions, retention was tested 6-10 hrs after ECT (compare to 104 min and 24 hrs in Kroes et al.).

A separate group of patients (n=9) was tested on their remote memories for old TV shows under three conditions: (1) 6-10 hrs after ECT; (2) 14-18 hrs before ECT and again with the same questions 6-10 hr after ECT; (3) Less than 10 min before ECT and again with the same questions 6-10 hrs after ECT (the reminder procedure).

The critical result is that the memory reactivation procedure did not impair performance (bar graphs A vs. R below). In both of these conditions, material was learned 14-18 hrs before ECT. This is in contrast to the findings of Kroes et al. (2013).

Fig. 1 (modified from Squire et al., 1976). Results from (A) 32-item recognition memory test, and (B) paired-associate learning test, under three conditions in conjunction with the patients' first 3 ECT sessions. Retention was significantly impaired in Condition B (initial learning 3-10 min before ECT). The reminder procedure (Condition R) caused no impairment in performance relative to Condition A.

Squire and colleagues (1976) concluded that “...the results provide no evidence that the presentation of previously learned material just prior to ECT increases its vulnerability to disruption.” Similar results were observed in the patient group tested on their knowledge of old TV shows: “the results clearly indicate that amnesia for remote memory did not occur when remote memory was evoked prior to ECT.”

The final conclusions [clairvoyantly] throw cold water on the study published 37 years later:

However, you'll probably notice some differences between the two studies. Kroes et al. pointed out that their effect was observed at a 24 hr retention interval, while Squire et al. only tested at 6-10 hrs (perhaps not long enough to disrupt reconsolidation). The Squire stimuli were neutral in valence, whereas the Kroes stimuli were emotional (and perhaps more susceptible to disruption). There were also differences in the patient groups (Squire's were younger, mean=39 yrs), anesthesia used, electrode locations, and ECT parameters (likely to be way more potent in the earlier study, which would predict worse amnesia). An unfortunate side effect of ECT is memory impairment, although other studies claim the opposite.

Certainly, subjective cognitive complaints after ECT are very common. For a first hand look at some of the more devastating effects, watch the powerful video below. For a lighthearted and critically acclaimed look at fictional memory erasure, watch Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

References

Kroes MC, Tendolkar I, van Wingen GA, van Waarde JA, Strange BA, & Fernández G (2013). An electroconvulsive therapy procedure impairs reconsolidation of episodic memories in humans. Nature neuroscience PMID: 24362759

Squire LR, Slater PC, & Chace PM (1976). Reactivation of recent or remote memory before electroconvulsive therapy does not produce retrograde amnesia. Behavioral biology, 18 (3), 335-43 PMID: 1016174

Liz Spikol (of The Trouble With Spikol fame) tries to explain the confusion and the loss of self she felt after waking up from ECT.

"After the ECT, I did not know how to use a toothbrush. And that lasted for months."

- Liz Spikol (at 9:28)

- Psychologists Find A Drug-free Way For Fears To Be Unlearned

In an exciting breakthrough for psychological science, researchers in the United States have demonstrated a drug-free way to prevent the return of a learned fear. Similar memory modification effects have been observed before, but these experiments have...

- Interfering With Traumatic Memories Of The Boston Marathon Bombings

The Boston Marathon bombings of April 15, 2013 killed three people and injured hundreds of others near the finish line of the iconic footrace. The oldest and most prominent marathon in the world, Boston attracts over 20,000 runners and 500,000 spectators....

- The Unique Case Of “50 First Dates” Amnesia

Scene from 50 First Dates with Drew Barrymore and Adam Sandler. 50 First Dates maintains a venerable movie tradition of portraying an amnesiac syndrome that bears no relation to any known neurological or psychiatric condition (Baxendale, 2004).That isn't...

- Everything Is Wrong

...about protein synthesis and memory formation, apparently. In keeping with the general theme of propranolol as a "memory eraser," a brand new iconoclastic paper (Canal, Chang, & Gold, 2007) claims that massive fluctuations in neurotransmitter levels...

- Scents & Sleep

The New York Times article Study Uncovers Memory Aid: A Scent During Sleep says that smells may help us remember things better. They quote a study recently published in Science: "The smell of roses — delivered to people’s nostrils as they studied...

Neuroscience

How Can We Forget?

** This post is meant to be read in tandem with its more complimentary cousin, Electroconvulsive Therapy Impairs Memory Reconsolidation, at The Neurocomplimenter. **

spECTrum 5000Q® ECT device (MECTA)

Bad memories haunt a significant number of people with serious mental illnesses, such as chronic major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). If it were possible to undergo an experimental procedure that selectively impairs your memory for an extremely unpleasant event, would you do it? If this sounds like the plot of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, you're not alone.

A pet peeve of mine is reference to this excellent but far-fetched film in scientific journals and popular media coverage of “memory erasure.” The idea that it's possible to selectively remove a complex autobiographical memory that has become intimately entwined with the fabric of our constructed selves is utter science fiction.

At some level, even Michel Gondry knew it. One incident in Eternal Sunshine is suggestive of how memories might actually be stored. It was after one of the main characters (Joel) had his memories of his ex-girlfriend Clementine erased, and he couldn't remember who Huckleberry Hound was. He had associated the cartoon character and the song "Darling Clementine" with her. That resembles a semantic network, where an overlapping network of neurons and synapses code different but semantically related things. Take out all episodic and semantic memories of Clementine, and knowledge of Huckleberry Hound goes with it.

The latest incarnation of this particular memory erasure meme was provoked by publication of a paper (Kroes et al., 2013) that examined the process of memory reconsolidation in depressed patients administered a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Here are some of the headlines:

Zapping the brain can help to spot-clean nasty memories

Absolutely shocking: electrocuting brain can wipe unpleasant memories

Unwanted Memories Erased in Electroconvulsive Therapy Experiment

Shocking Memories Away

My companion post at The Neurocomplimenter reviews the literature on memory reconsolidation and describes the experiment of Kroes et al. (2013) in some detail. What I'd like to do here is to point out possible weaknesses in the results that could undermine the authors' conclusions. I'll also discuss a much earlier ECT study which did not support the notion that reactivated memories are especially vulnerable to disruption (Squire et al., 1976).

To briefly reiterate the methods used in the new paper (Kroes et al., 2013), the participants were 39 patients with moderate to severe major depression. They were either at the end of an acute treatment cycle or receiving maintenance ECT. The study used a between-subjects design with three different experimental conditions, with patients randomly assigned to one of the three groups (n=13 in each). The within-subjects factor was whether or not the patients received a reminder of previously learned material before treatment.

All participants learned two different emotionally charged slide stories with audio narration, each consisting of 11 images. In one, a boy is in an accident that severs his feet, which are reattached at the hospital. In the other, two sisters leave their home at night, and one is kidnapped at knife point and attacked by an escaped convict.

Memory for one of the stories was reactivated a week later by presenting part of the first slide, and then giving a test for this slide. Only four minutes later, Groups A and B were anesthetized and received ECT. Group C received their ECT treatment at a later date. The final memory test for Groups A and C was 24 hrs after the reminder, while Group B was tested as soon as they woke up from the procedure (mean = 104 min later). The final test consisted of 40 multiple choice questions about each of the stories.

The basic idea is that reconsolidation of the reactivated story isn't complete within 104 min, so Group B's test performance should be the same for the two stories. In contrast, reconsolidation is complete by 24 hrs, so for Group A the disruptive effect of ECT should selectively impair memory for the transiently reactivated story, which is in a labile state (relative to the "consolidated" story learned 7 days earlier).

Is that what was observed? Statistically speaking, yes. But two patients in Group B (out of 13 total) performed very well on the reactivated story (see purple box in the figure below).

Fig. 1 (modified from Kroes et al. 2013). ECT disrupts reconsolidation. Memory scores on the multiple choice test are expressed as percentage correct (y axis). Memory for the reactivated story shown in solid bars and non-reactivated story in open bars. Each circle is the score for an individual patient. The horizontal dotted line is chance performance. Group A is in red, Group B in blue, and Group C in orange. Edited to add: The purple box highlights 2 outliers in Group B who could be driving the major effect.

If these two individuals are omitted, would the difference between Groups A and B still be significant? This is the key finding of the paper, that memory for the reactivated story is no better than chance if ECT disrupts reconsolidation (a time-dependent process). Hence all the Eternal Sunshine / “memory erasure” headlines.

The purple boxes show that (1) the Reactivation x Group interaction squeaks in at just barely significant (p=.049); and (2) the Group A vs. Group B comparison for the reactivated story is p=.042. Clearly, it would be nice to include twice as many patients in each group. But it took the authors 3.5 years to recruit their final total of n=39.

This type of study is not easy to pull off, which is why I applaud the authors (and the patients) for such an ambitious undertaking. I thought it was a very clever idea as well, but not an original one as it turns out.

In the 1970s and 80s, Dr. Larry Squire and his colleagues published a series of papers on ECT and memory. The one I'll describe here takes a similar approach to Kroes et al. by testing previously learned material after ECT, and by giving a memory reminder just before the treatment (Squire et al., 1976).

Squire et al. (1976) used a completely within-subjects design (n=12) that manipulated the pre-ECT learning interval (14-18 hrs vs. 3-10 min). The third condition presented a memory reminder 3-10 min before ECT for material learned 14-18 hrs previously. Completely different stimuli were used each time, and the order of conditions was counterbalanced. The memory tests were recognition memory for a set of 32 previously learned items (common objects, common words, yearbook photos, and nonsense drawings), and paired associates (producing the correct target for 18 previously learned cue-target pairs). In all conditions, retention was tested 6-10 hrs after ECT (compare to 104 min and 24 hrs in Kroes et al.).

A separate group of patients (n=9) was tested on their remote memories for old TV shows under three conditions: (1) 6-10 hrs after ECT; (2) 14-18 hrs before ECT and again with the same questions 6-10 hr after ECT; (3) Less than 10 min before ECT and again with the same questions 6-10 hrs after ECT (the reminder procedure).

The critical result is that the memory reactivation procedure did not impair performance (bar graphs A vs. R below). In both of these conditions, material was learned 14-18 hrs before ECT. This is in contrast to the findings of Kroes et al. (2013).

Fig. 1 (modified from Squire et al., 1976). Results from (A) 32-item recognition memory test, and (B) paired-associate learning test, under three conditions in conjunction with the patients' first 3 ECT sessions. Retention was significantly impaired in Condition B (initial learning 3-10 min before ECT). The reminder procedure (Condition R) caused no impairment in performance relative to Condition A.

Squire and colleagues (1976) concluded that “...the results provide no evidence that the presentation of previously learned material just prior to ECT increases its vulnerability to disruption.” Similar results were observed in the patient group tested on their knowledge of old TV shows: “the results clearly indicate that amnesia for remote memory did not occur when remote memory was evoked prior to ECT.”

The final conclusions [clairvoyantly] throw cold water on the study published 37 years later:

The present findings also have important clinical implications. The reactivation phenomenon described in experimental animals has raised the possibility that it might be therapeutically advantageous to evoke depressive ideation just prior to treatment, in order to produce amnesia for this ideation. The results reported here strongly suggest that this procedure would be ineffective.

However, you'll probably notice some differences between the two studies. Kroes et al. pointed out that their effect was observed at a 24 hr retention interval, while Squire et al. only tested at 6-10 hrs (perhaps not long enough to disrupt reconsolidation). The Squire stimuli were neutral in valence, whereas the Kroes stimuli were emotional (and perhaps more susceptible to disruption). There were also differences in the patient groups (Squire's were younger, mean=39 yrs), anesthesia used, electrode locations, and ECT parameters (likely to be way more potent in the earlier study, which would predict worse amnesia). An unfortunate side effect of ECT is memory impairment, although other studies claim the opposite.

Certainly, subjective cognitive complaints after ECT are very common. For a first hand look at some of the more devastating effects, watch the powerful video below. For a lighthearted and critically acclaimed look at fictional memory erasure, watch Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

References

Kroes MC, Tendolkar I, van Wingen GA, van Waarde JA, Strange BA, & Fernández G (2013). An electroconvulsive therapy procedure impairs reconsolidation of episodic memories in humans. Nature neuroscience PMID: 24362759

Squire LR, Slater PC, & Chace PM (1976). Reactivation of recent or remote memory before electroconvulsive therapy does not produce retrograde amnesia. Behavioral biology, 18 (3), 335-43 PMID: 1016174

Liz Spikol (of The Trouble With Spikol fame) tries to explain the confusion and the loss of self she felt after waking up from ECT.

"After the ECT, I did not know how to use a toothbrush. And that lasted for months."

- Liz Spikol (at 9:28)

- Psychologists Find A Drug-free Way For Fears To Be Unlearned

In an exciting breakthrough for psychological science, researchers in the United States have demonstrated a drug-free way to prevent the return of a learned fear. Similar memory modification effects have been observed before, but these experiments have...

- Interfering With Traumatic Memories Of The Boston Marathon Bombings

The Boston Marathon bombings of April 15, 2013 killed three people and injured hundreds of others near the finish line of the iconic footrace. The oldest and most prominent marathon in the world, Boston attracts over 20,000 runners and 500,000 spectators....

- The Unique Case Of “50 First Dates” Amnesia

Scene from 50 First Dates with Drew Barrymore and Adam Sandler. 50 First Dates maintains a venerable movie tradition of portraying an amnesiac syndrome that bears no relation to any known neurological or psychiatric condition (Baxendale, 2004).That isn't...

- Everything Is Wrong

...about protein synthesis and memory formation, apparently. In keeping with the general theme of propranolol as a "memory eraser," a brand new iconoclastic paper (Canal, Chang, & Gold, 2007) claims that massive fluctuations in neurotransmitter levels...

- Scents & Sleep

The New York Times article Study Uncovers Memory Aid: A Scent During Sleep says that smells may help us remember things better. They quote a study recently published in Science: "The smell of roses — delivered to people’s nostrils as they studied...