Neuroscience

Two Buck Chuck

A very important study appeared online yesterday in PNAS, as reported in this erroneously-titled AP story:

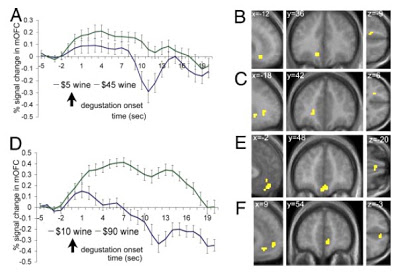

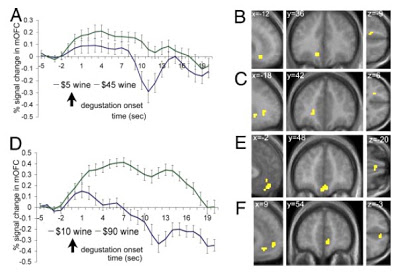

Fig. 2 of Plassmann et al. (2008). Activation maps are shown at a threshold of P less than 0.001 uncorrected and with an extend threshold of five voxels.

So they've demonstrated that "pleasantness" (i.e., mOFC activity) is influenced by price. Similar activations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, visual cortex, middle temporal gyrus, and cingulate gyrus for wine 1 and in the amygdala, lateral OFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior and middle temporal gyrus, and posterior cingulate cortex for wine 2 were under rug swept.

What else have we learned?

2002 Opus One

2002 Opus One

Footnote

1 Who paid for this $90 wine? Perhaps it was the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Neurobiological Reward - $5,998,512 - Jun. 2006), as opposed to the National Science Foundation (SES-0134618).

Reference

Plassmann H, O'Doherty J, Shiv B, Rangel A. (2008). Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Published online before print January 14, 2008.

Despite the importance and pervasiveness of marketing, almost nothing is known about the neural mechanisms through which it affects decisions made by individuals. We propose that marketing actions, such as changes in the price of a product, can affect neural representations of experienced pleasantness. We tested this hypothesis by scanning human subjects using functional MRI while they tasted wines that, contrary to reality, they believed to be different and sold at different prices. Our results show that increasing the price of a wine increases subjective reports of flavor pleasantness as well as blood-oxygen-level-dependent activity in medial orbitofrontal cortex, an area that is widely thought to encode for experienced pleasantness during experiential tasks. The paper provides evidence for the ability of marketing actions to modulate neural correlates of experienced pleasantness and for the mechanisms through which the effect operates.

See also:

EP & neuroeconomics: how thinking about the price of wine tweaks your brain's sensation of pleasure

Higher price makes cheap wine taste better

- Wine Tastes Like The Music You're Listening To

We often think of our sensory modalities as like separate channels. In fact, there's a lot of cross-talk and interference between them. Consider how the prick of a needle is more painful if you watch it go in. Under-researched in this respect is the...

- Practising Describing Wines Could Help You Become A Connoisseur

"Hmm, it tastes peachy, gutsy, with a pinch of wild berries," the wine connoisseur says after swirling the Chiraz round her mouth and pulling a few rubbery facial expressions. Such attempts to verbalise the flavour of wine may come in for a deserved degree...

- Ouch, That's Expensive!

As well as hurting your wallet, your brain expects an expensive product to cause you pain too. Researchers have found that in terms of brain activity, whether or not we choose to make a purchase is reflected in a trade-off between regions of the brain...

- Give And Take

Most of us have had the experience of opening yet another present of socks or hankies from a well-intentioned older relative. But even among friends, why is it that people giving presents so often get it wrong? Norwegian psychologists Karl Teigen, Marina...

- Grant Not Funded? Let's Go Shopping!

And now presenting, The Godiva Chocolate study!! (or the generic version, an fMRI study of chocolate purchasing decisions). from Knutson et al. (2007) Coverage from Scientific American: This Is Your Brain on Shopping An fMRI study determines where the...

Neuroscience

Delineation of the Two Buck Chuck Neocortical Circuitry

Two Buck Chuck

A very important study appeared online yesterday in PNAS, as reported in this erroneously-titled AP story:

Raising Prices Enhances Wine SalesIn their tricky fMRI experiment, the authors weren't really interested in delineating the neocortical (or subcortical) circuitry underlying marketing actions. Instead, their interest was in one particular cortical region within the frontal lobes, hypothesizing that

By RANDOLPH E. SCHMID

WASHINGTON (AP) — Apparently, raising the price really does make the wine taste better. At least that seems to be the result of a taste test. The part of the brain that reacts to a pleasant experience responded more strongly to pricey wines than cheap ones — even when tasters were given the same vintage in disguise.

Antonio Rangel and colleagues at California Institute of Technology thought the perception that higher price means higher quality could influence people, so they decided to test the idea.

They asked 20 people to sample wine while undergoing functional MRIs of their brain activity. The subjects were told they were tasting five different Cabernet Sauvignons sold at different prices.

However, there were actually only three wines sampled, two being offered twice, marked with different prices.

A $90 wine1 was provided marked with its real price and again marked $10, while another was presented at its real price of $5 and also marked $45.

The testers' brains showed more pleasure at the higher price than the lower one, even for the same wine, Rangel reports...

higher taste expectations would lead to higher activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), an area of the brain that is widely thought to encode for actual experienced pleasantness.Lo and behold, that is what they found! Panel A shows the time course of mOFC activation, with greater BOLD signal change when consuming the cheap $5 wine disguised as a $45/bottle wine. Panel D shows with greater BOLD signal change when consuming the expensive $90/bottle wine marketed as such, and much less activity when it masquerades as the $10 wine.

Fig. 2 of Plassmann et al. (2008). Activation maps are shown at a threshold of P less than 0.001 uncorrected and with an extend threshold of five voxels.

So they've demonstrated that "pleasantness" (i.e., mOFC activity) is influenced by price. Similar activations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, visual cortex, middle temporal gyrus, and cingulate gyrus for wine 1 and in the amygdala, lateral OFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior and middle temporal gyrus, and posterior cingulate cortex for wine 2 were under rug swept.

What else have we learned?

...when tasters didn't know any price comparisons, they [20 Cal Tech students] rated the $5 wine as better than any of the others sampled.

"We were shocked," Rangel said in a telephone interview. [NOTE: why were you shocked? Did you think your subjects would be wine connoisseurs?] "I think it was because the flavor was stronger and our subjects were not very experienced."

He added that wine professionals would probably be able to differentiate the better wine — "one would hope."

2002 Opus One

2002 Opus OneFootnote

1 Who paid for this $90 wine? Perhaps it was the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Neurobiological Reward - $5,998,512 - Jun. 2006), as opposed to the National Science Foundation (SES-0134618).

Reference

Plassmann H, O'Doherty J, Shiv B, Rangel A. (2008). Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Published online before print January 14, 2008.

Despite the importance and pervasiveness of marketing, almost nothing is known about the neural mechanisms through which it affects decisions made by individuals. We propose that marketing actions, such as changes in the price of a product, can affect neural representations of experienced pleasantness. We tested this hypothesis by scanning human subjects using functional MRI while they tasted wines that, contrary to reality, they believed to be different and sold at different prices. Our results show that increasing the price of a wine increases subjective reports of flavor pleasantness as well as blood-oxygen-level-dependent activity in medial orbitofrontal cortex, an area that is widely thought to encode for experienced pleasantness during experiential tasks. The paper provides evidence for the ability of marketing actions to modulate neural correlates of experienced pleasantness and for the mechanisms through which the effect operates.

See also:

EP & neuroeconomics: how thinking about the price of wine tweaks your brain's sensation of pleasure

Higher price makes cheap wine taste better

- Wine Tastes Like The Music You're Listening To

We often think of our sensory modalities as like separate channels. In fact, there's a lot of cross-talk and interference between them. Consider how the prick of a needle is more painful if you watch it go in. Under-researched in this respect is the...

- Practising Describing Wines Could Help You Become A Connoisseur

"Hmm, it tastes peachy, gutsy, with a pinch of wild berries," the wine connoisseur says after swirling the Chiraz round her mouth and pulling a few rubbery facial expressions. Such attempts to verbalise the flavour of wine may come in for a deserved degree...

- Ouch, That's Expensive!

As well as hurting your wallet, your brain expects an expensive product to cause you pain too. Researchers have found that in terms of brain activity, whether or not we choose to make a purchase is reflected in a trade-off between regions of the brain...

- Give And Take

Most of us have had the experience of opening yet another present of socks or hankies from a well-intentioned older relative. But even among friends, why is it that people giving presents so often get it wrong? Norwegian psychologists Karl Teigen, Marina...

- Grant Not Funded? Let's Go Shopping!

And now presenting, The Godiva Chocolate study!! (or the generic version, an fMRI study of chocolate purchasing decisions). from Knutson et al. (2007) Coverage from Scientific American: This Is Your Brain on Shopping An fMRI study determines where the...