Deal, No Deal, or Dots?

OR: Is Perceptual Decision Making in Primate LIP Equivalent to Financial Decision Making Under Risk?

In the universally familiar game show Deal or No Deal, contestants choose from among 26 briefcases held by 26 models. Each of these briefcases contains a different amount of money ranging from $0.01 to $1,000,000. The contestant begins by choosing one briefcase, then starts selecting other cases to open, hoping to reveal small cash amounts because this will improve the odds of winning the $1 million. After a predetermined number of cases are opened, 'the Banker' tries to tempt the player to exchange her case for an amount of instant cash. The player must either stick with her original briefcase choice ('No Deal'), or make a 'Deal' with the Banker to accept his cash offer in exchange for whatever dollar amount is in the chosen case.

The show is a terrific example of financial decision making under risk. Nobel prize recipient Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky developed the idea of prospect theory to explain how people decide between alternatives that involve risk, when the outcome is uncertain but the probabilities are known (or estimated). Their highly influential paper (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) framed these ideas, which provided an alternative to the expected utility hypothesis:

The show is a terrific example of financial decision making under risk. Nobel prize recipient Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky developed the idea of prospect theory to explain how people decide between alternatives that involve risk, when the outcome is uncertain but the probabilities are known (or estimated). Their highly influential paper (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) framed these ideas, which provided an alternative to the expected utility hypothesis:

What does any of this have to do with dots??

The University of Rochester issued an egregiously erroneous press release to accompany the publication of a new paper in Neuron (Beck et al., 2008):

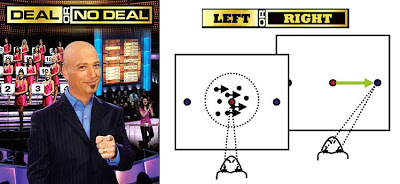

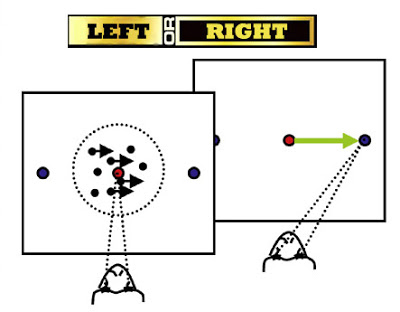

Our Unconscious Brain Makes the Best Decisions PossibleLet's see, the study was done in monkeys (not humans), and the results said absolutely nothing about proving the brain is "hard-wired" to make the best decisions possible. The paper used computational methods to analyze the spike trains of neurons in the lateral intraparietal (LIP) area of monkeys who were trained to make motion discriminations. The original data were taken from the paper of Anne Churchland et al. (2008). One of the experimental tasks is illustrated below.New Research Shows the Human Brain Computes Extremely Well—Given What it Knows

Researchers at the University of Rochester have shown that the human brain—once thought to be a seriously flawed decision maker—is actually hard-wired to allow us to make the best decisions possible with the information we are given.

Figure 1A (Beck et al., 2008). Binary decision making. The subject must decide whether the dots are moving to the right or to the left. Only a fraction of the dots are moving to the right or the left coherently (black arrows). The other dots move in random directions. The animal indicates its response by moving its eyes in the perceived direction (green arrow).

Another variant of the task involved four choices instead of two (Churchland et al., 2008). In the Neuron paper, Beck et al. described a neural network model of decision making in these tasks. Although the motion direction task has been extensively studied in both animals and humans, the reported model is clearly based on recordings of LIP neurons in rhesus monkeys.

Back to paragraph #2 of the press release:

Neuroscientists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky received a 2002 Nobel Prize for their 1979 research that argued humans rarely make rational decisions. Since then, this has become conventional wisdom among cognition researchers.Kahneman and Tversky are/were (respectively) psychologists, not neuroscientists, and Tversky did not receive the Nobel prize. Perceptual discrimination of motion direction is not the same thing as financial decision making under risk, with its cognitive and affective elements. Although the monkeys were rewarded for correct decisions, reward functions were not a part of the network model. The authors summarized the significance of their work as follows:

First, we show that for Poisson-like distributions, optimal evidence accumulation can be performed through simple integration of neural activities, while optimal response selection can be implemented through attractor dynamics. Second, we show (again for Poisson-like distributions of neural activity) that neurons encode the posterior probability distribution over the variables of interest at all times. This latter contribution has far-reaching implications, since it suggests that neurons implicated in simple perceptual decisions represent quantities that are directly relevant to inference, confidence, and belief.However, they didn't directly extrapolate their results to behavioral economics, and they didn't cite Kahneman and Tversky. Neverthess, the press release by the Senior Science Press Officer continues:

Contrary to Kahnneman and Tversky's research, Alex Pouget, associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the University of Rochester, has shown that people do indeed make optimal decisions—but only when their unconscious brain makes the choice.At the risk of sounding pedantic, people did not make the decisions (monkeys did), and there was nary a mention of conscious vs. unconscious processing in the paper.

I don't know if there would be any differences in the results if the monkeys were told the percentages up front... but you can watch Professor Kahneman discuss Decision Making and Rationality in Deal or No Deal Decisions, now showing on Channel N."A lot of the early work in this field was on conscious decision making, but most of the decisions you make aren't based on conscious reasoning," says Pouget. "You don't consciously decide to stop at a red light or steer around an obstacle in the road. Once we started looking at the decisions our brains make without our knowledge, we found that they almost always reach the right decision, given the information they had to work with."

Pouget says that Kahneman's approach was to tell a subject that there was a certain percent chance that one of two choices in a test was "right." This meant a person had to consciously compute the percentages to get a right answer—something few people could do accurately.

. . .

"We've been developing and strengthening this hypothesis for years—how the brain represents probability distributions," says Pouget. "We knew the results of this kind of test fit perfectly with our ideas, but we had to devise a way to see the neurons in action. We wanted to see if, in fact, humans are really good decision makers after all, just not quite so good at doing it consciously. Kahneman explicitly told his subjects what the chances were, but we let people's unconscious mind work it out. It's weird, but people rarely make optimal decisions when they are told the percentages up front."

References

J BECK, W MA, R KIANI, T HANKS, A CHURCHLAND, J ROITMAN, M SHADLEN, P LATHAM, A POUGET (2008). Probabilistic Population Codes for Bayesian Decision Making Neuron, 60 (6), 1142-1152 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.021

Churchland AK, Kiani R, Shadlen MN. (2008). Decision-making with multiple alternatives. Nat Neurosci. 11:693-702.

Kahneman D, Tversky A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47: 263-291.

- Want To Make A Complicated Decision? Keep Thinking

"Want to make a complicated decision? Just stop thinking", was one of hundreds of headlines spawned by a study published in 2006 by Ap Dijksterhuis and colleagues. The team of Dutch researchers reported that students made "better" decisions after being...

- Watch Laurie Santos Discuss Her Research Showing That Monkeys, Like Humans, Can Be Extremely Irrational

A while back we reported on some research that showed monkeys and young children demonstrate the effects of cognitive dissonance in the same way that adult humans do. In particular, monkeys who were forced to make an arbitrary choice between equally appealing...

- Gambling On Obscurity

Well, after a year of blogging here at The Neurocritic, I thought I might still get away with a snarky, end-of-week, throwaway post about a Science paper whose press coverage was overshadowed by the Great Insula Smokeout. Wrong! It appears that one of...

- So-called "lizard Brains" And The Stock Market

This evening's NewsHour with Jim Lehrer on PBS incuded a segment entitled Using Your Brain: "A report on what is really going on inside our heads when we make economic decisions. Researchers are beginning to understand how the pre-frontal cortex and...

- The Dread Zone

I encountered this research about the neurobiology of dread twice recently — in the New York Times and on Science Friday (mp3). Science Friday interviewed Gregory Berns (professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory), who used fMRI to determine...