Neuroscience

Playing dead game -- A craze called the "playing dead game" has swept this nation where people of all ages stage elaborate death scenes everyplace.

Believing That We're Dead

Cotard's Syndrome is the delusional belief that one is dead or missing internal organs or other body parts (Debruyne et al., 2009). Those who suffer from this "delusion of negation" deny their own existence. The eponymous French neurologist Jules Cotard called it le délire de négation ("negation delirium").

Cotard's syndrome has been observed in mentally ill persons with psychotic disorders (such as schizophrenia and psychotic depression), as well as in neurological patients with acquired brain damage. In a review of 100 cases, Berrios and Luque (1995) found that:

In their overview, Debruyne et al., 2009 presented two cases with distinctively different outcomes:

Delusions of Death in a Patient with Right Hemisphere Infarction

Does the right hemisphere play a unique role in maintaining a sense of self? A new case study by Nishio and Mori (2012) described a 69 year old patient who suffered a stroke affecting portions of the right frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and right thalamus. A neurological exam a week later revealed severe hemispatial neglect of the left side of space, left sided weakness, motor neglect of his left limbs, and impaired senses of pain, cold, touch, vibration, and position on the left side of his body. These symptoms are typical of such a large right hemisphere lesion (see below).1

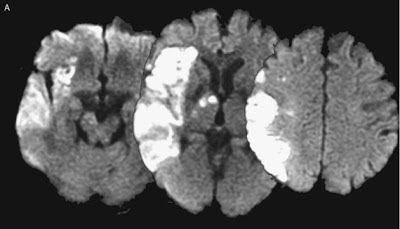

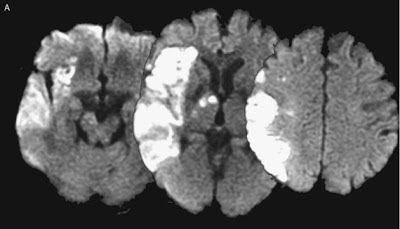

FIGURE 1. (Nishio & Mori, 2012). Magnetic resonance images of the patient’s brain, taken just after the onset of the stroke. The right side of the brain appears on the left side of the scans. A, Transverse diffusion-weighted images show fresh infarcts involving the right-frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and thalamus.

What was unusual were other aspects of his behavioral presentation:

As time passed, his delusions of death dissipated, yet in retrospect he characterized these delusions as real:

The authors discussed the case in relation to other delusional misidentification syndromes such as Capgras syndrome, where the patient believes their loved ones have been replaced by nearly identical duplicates or impostors. One functional interpretation of Capgras is that a disconnection between facial recognition and affective processes has occurred, such that the person no longer experiences the feelings of familiarity and warmth towards their significant others. In a similar fashion, some cases of Cotard could result from a lack of familiarity with or detachment from one's self, which is then interpreted as being dead or no longer existing.

Why did this particular patient show the Cotard delusion, whereas other people with similar right hemisphere strokes have not? Where is the pathology in psychiatric patients with Cotard's, who comprise the bulk of case reports? For that matter, will we be able to develop neuroscientific explanations for these questions and construct something resembling a functional neuroanatomy of the self?

Are you really your connectome??

L7 - Pretend We're Dead, directed by Modi Frank.

Footnote

1 Interestingly, the patient seemed to present with a relatively pure case of Cotard type I. His delusion was restricted to death, as he did not deny the existence of body parts or of his left-sided weakness. Both of these are relatively common with similar right hemisphere strokes.

References

Berrios GE, Luque R. (1995). Cotard's syndrome: analysis of 100 cases. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 91:185-8.

Debruyne H, Portzky M, Van den Eynde F, Audenaert K (2009). Cotard's syndrome: a review. Current psychiatry reports, 11 (3), 197-202. PMID: 19470281

Nishio Y, Mori E (2012). Delusions of Death in a Patient with Right Hemisphere Infarction. Cognitive and behavioral neurology. PMID: 23103861

Playing dead -- Chuck Lamb is the “dead body guy”. He enjoys playing dead and his tryings to “perform” in movies made him more famous than his actually doing that.

Playing dead -- Chuck Lamb is the “dead body guy”. He enjoys playing dead and his tryings to “perform” in movies made him more famous than his actually doing that.

- Hiring Private Detectives To Investigate Paranoid Delusions

Vaughan Bell: "In 1684, the famous writer, Nathaniel Lee, was becoming increasingly disturbed and was promptly admitted to Bethlem Hospital. While protesting his sanity, he described the situation as one where 'they called me mad, and I called them...

- Who Replaced All My Things?

Capgras syndrome – in which the patient believes their friends and relatives have been replaced by impersonators – was first described in 1923 by the French psychiatrist J.M.J. Capgras in a paper with J. Reboul-Lachaux. Now Alireza Nejad and Khatereh...

- The Long-term Benefits Of Cbt For Schizophrenia

Not only can cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) provide sufferers of schizophrenia with additional benefits above and beyond those gained from taking anti-psychotic medication, but some of these benefits continue to persist two years later. Furthermore,...

- Capgras For Cats And Canaries

Capgras syndrome is the delusion that a familiar person has been replaced by a nearly identical duplicate. The imposter is usually a loved one or a person otherwise close to the patient. Originally thought to be a manifestation of schizophrenia and other...

- Shooting The Phantom Head (perceptual Delusional Bicephaly)

I have two headsWhere's the man, he's late --Throwing Muses, Devil's Roof Medical journals are enlivened by case reports of bizarre and unusual syndromes. Although somatic delusions are relatively common in schizophrenia, reports of hallucinations...

Neuroscience

Cotard's Syndrome: Not Pretending That We're Dead

Playing dead game -- A craze called the "playing dead game" has swept this nation where people of all ages stage elaborate death scenes everyplace.

Believing That We're Dead

Cotard's Syndrome is the delusional belief that one is dead or missing internal organs or other body parts (Debruyne et al., 2009). Those who suffer from this "delusion of negation" deny their own existence. The eponymous French neurologist Jules Cotard called it le délire de négation ("negation delirium").

Cotard's syndrome has been observed in mentally ill persons with psychotic disorders (such as schizophrenia and psychotic depression), as well as in neurological patients with acquired brain damage. In a review of 100 cases, Berrios and Luque (1995) found that:

Depression was reported in 89% of subjects; the most common nihilistic delusions concerned the body (86%) and existence (69%). Anxiety (65%) and guilt (63%) were also common, followed by hypochondriacal delusions (58%) and delusions of immortality (55). An exploratory factor analysis extracted 3 factors: psychotic depression, Cotard type I and Cotard type II. The psychotic depression factor included patients with melancholia and few nihilistic delusions. Cotard type 1 patients, on the other hand, showed no loadings for depression or other disease and are likely to constitute a pure Cotard syndrome whose nosology may be closer to the delusional than the affective disorders. Type II patients showed anxiety, depression and auditory hallucinations and constitute a mixed group.

In their overview, Debruyne et al., 2009 presented two cases with distinctively different outcomes:

1. An 88-year-old man with mild cognitive impairment was admitted to our hospital for treatment of a severe depressive episode. He was convinced that he was dead and felt very anxious because he was not yet buried. This delusion caused extreme suffering and made outpatient treatment impossible. Treatment with sertraline, 50 mg, and risperidone, 1 mg, resulted in complete remission of the depressive episode and nihilistic delusions...In the 46 year old patient, MRI and SPECT findings were negative, but her neuropsychological testing was suggestive of right hemisphere dysfunction.

2. A 46-year-old woman with known rapid-cycling bipolar disorder ... presented with a depressive episode with psychotic features. Her nihilistic delusions were compatible with Cotard’s syndrome. She had the constant experience of having no identity or “self” and being only a body without content. In addition, she was convinced that her brain had vanished, her intestines had disappeared, and her whole body was translucent. ... The following pharmacologic treatments previously had been used to treat this patient, without consistent effect: lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, clozapine, pimozide, sulpiride, clomipramine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, and venlafaxine. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was also used without effect. The nihilistic delusions disappeared in this patient, but a mood switch to a hypomanic episode occurred...

Delusions of Death in a Patient with Right Hemisphere Infarction

Does the right hemisphere play a unique role in maintaining a sense of self? A new case study by Nishio and Mori (2012) described a 69 year old patient who suffered a stroke affecting portions of the right frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and right thalamus. A neurological exam a week later revealed severe hemispatial neglect of the left side of space, left sided weakness, motor neglect of his left limbs, and impaired senses of pain, cold, touch, vibration, and position on the left side of his body. These symptoms are typical of such a large right hemisphere lesion (see below).1

FIGURE 1. (Nishio & Mori, 2012). Magnetic resonance images of the patient’s brain, taken just after the onset of the stroke. The right side of the brain appears on the left side of the scans. A, Transverse diffusion-weighted images show fresh infarcts involving the right-frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and thalamus.

What was unusual were other aspects of his behavioral presentation:

...He criticized his doctors, nurses, and rehabilitation therapists, and complained bitterly about the hospital’s food and oxygen. He falsely believed that his brother-in-law, previously a director of another hospital, was to blame for this hospital’s flaws. He was treated with mianserin (10 mg/day) and quetiapine (25 mg/day); his irritability and agitation subsided within 2 to 3 weeks. During that time, we became aware that the patient was suffering from several delusional misidentifications. He thought that Kim Jong-il, then the leader of North Korea, was staying on the floor below his own, and that his physical therapist was a grandson of Puyi, the last Emperor of China...

A month after the onset of his symptoms, by which time his motor and cognitive symptoms had gradually improved, he began complaining regularly of feelings of unreality, and asked his wife whether he was alive or dead. He said to his doctor, “I guess I am dead. I’d like to ask for your opinion.” Later, his conviction about death became firmer. He said, “My death certificate has been registered. You are walking with a dead man,” and “I am dead. I will receive a death certificate for me from my doctor and have to bring it to the city office early next week.”

His discussion of his demise was not associated with a depressed mood or feelings of fear. When his doctor asked him whether a dead man could speak, he understood that his words defied logic, but he could not change his thinking.

As time passed, his delusions of death dissipated, yet in retrospect he characterized these delusions as real:

His delusion of being dead and his feelings of depersonalization gradually subsided and disappeared 4 months after the stroke. One year after the stroke, however, he still believed in the truth of the memories that he had formed during his delusional state. He said, “Now I am alive. But I was once dead at that time,” and “I saw Kim Jong-il in the hospital where I stayed.”

The authors discussed the case in relation to other delusional misidentification syndromes such as Capgras syndrome, where the patient believes their loved ones have been replaced by nearly identical duplicates or impostors. One functional interpretation of Capgras is that a disconnection between facial recognition and affective processes has occurred, such that the person no longer experiences the feelings of familiarity and warmth towards their significant others. In a similar fashion, some cases of Cotard could result from a lack of familiarity with or detachment from one's self, which is then interpreted as being dead or no longer existing.

Why did this particular patient show the Cotard delusion, whereas other people with similar right hemisphere strokes have not? Where is the pathology in psychiatric patients with Cotard's, who comprise the bulk of case reports? For that matter, will we be able to develop neuroscientific explanations for these questions and construct something resembling a functional neuroanatomy of the self?

Are you really your connectome??

L7 - Pretend We're Dead, directed by Modi Frank.

Footnote

1 Interestingly, the patient seemed to present with a relatively pure case of Cotard type I. His delusion was restricted to death, as he did not deny the existence of body parts or of his left-sided weakness. Both of these are relatively common with similar right hemisphere strokes.

The patient did not show asomatognosia (lack of awareness about the condition of part or all of his body), anosognosia (lack of awareness of his disability) for hemiplegia, or somatoparaphrenia (denial that a limb or a whole side belonged to his body).

References

Berrios GE, Luque R. (1995). Cotard's syndrome: analysis of 100 cases. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 91:185-8.

Debruyne H, Portzky M, Van den Eynde F, Audenaert K (2009). Cotard's syndrome: a review. Current psychiatry reports, 11 (3), 197-202. PMID: 19470281

Nishio Y, Mori E (2012). Delusions of Death in a Patient with Right Hemisphere Infarction. Cognitive and behavioral neurology. PMID: 23103861

- Hiring Private Detectives To Investigate Paranoid Delusions

Vaughan Bell: "In 1684, the famous writer, Nathaniel Lee, was becoming increasingly disturbed and was promptly admitted to Bethlem Hospital. While protesting his sanity, he described the situation as one where 'they called me mad, and I called them...

- Who Replaced All My Things?

Capgras syndrome – in which the patient believes their friends and relatives have been replaced by impersonators – was first described in 1923 by the French psychiatrist J.M.J. Capgras in a paper with J. Reboul-Lachaux. Now Alireza Nejad and Khatereh...

- The Long-term Benefits Of Cbt For Schizophrenia

Not only can cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) provide sufferers of schizophrenia with additional benefits above and beyond those gained from taking anti-psychotic medication, but some of these benefits continue to persist two years later. Furthermore,...

- Capgras For Cats And Canaries

Capgras syndrome is the delusion that a familiar person has been replaced by a nearly identical duplicate. The imposter is usually a loved one or a person otherwise close to the patient. Originally thought to be a manifestation of schizophrenia and other...

- Shooting The Phantom Head (perceptual Delusional Bicephaly)

I have two headsWhere's the man, he's late --Throwing Muses, Devil's Roof Medical journals are enlivened by case reports of bizarre and unusual syndromes. Although somatic delusions are relatively common in schizophrenia, reports of hallucinations...