Neuroscience

In the 1970s, the roboticist Masahiro Mori noticed a curious phenomenon. As robots became more human-like, their appeal increased but only up to a point. When their human likeness became too realistic (but still not perfect), their appeal plunged. Mori nicknamed this abrupt aversion "the uncanny valley", in reference to the shape of the graph mapping human-likeness and appeal. Are we born with this aversion to the almost-real or does it emerge later?

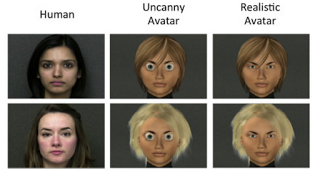

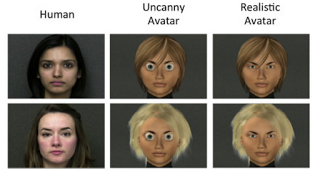

To find out, David Lewkowicz and Asif Ghazanfar presented nearly a hundred infants (aged between 6 to 12 months) with pairs of faces, to see which they would look at for longer. In the first study, the babies were shown a human face alongside a cartoon face (an "avatar") with enlarged goggle-eyes. The researchers said adults would find the avatar uncanny and would avoid looking at it. The key finding here was that six-month-olds spent more time looking at the uncanny avatar, whereas the twelve-month-olds, like adults, spent more time looking at the human face. Based on this dramatic contrast in preference, Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar said the uncanny valley effect emerges gradually between six and twelve months of age.

What was it about the faces that provoked this change in preference in the older babies? In two further studies, the researchers presented the babies with either a goggle-eyed uncanny avatar alongside a more realistic avatar face with normal-sized eyes, or with a human face alongside the realistic avatar. In the first case, all the babies, from 6 to 12 months, spent more time looking at the realistic avatar. In the second case, the babies of all ages spent equal amounts of time looking at the two faces.

What was it about the faces that provoked this change in preference in the older babies? In two further studies, the researchers presented the babies with either a goggle-eyed uncanny avatar alongside a more realistic avatar face with normal-sized eyes, or with a human face alongside the realistic avatar. In the first case, all the babies, from 6 to 12 months, spent more time looking at the realistic avatar. In the second case, the babies of all ages spent equal amounts of time looking at the two faces.

These results suggest that none of the babies could distinguish between the realistic avatar and a real human face, and that the older babies in the first study, and all the babies in the second study, must therefore have been using the enlarged eyes to distinguish the goggle-eyed avatar from a human face or realistic avatar face, respectively.

Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar said that the aversion to the goggle-eyed uncanny avatar likely emerged in the older babies as a consequence of their growing expertise with processing human faces, and their association of human faces with positive consequences. However, the older babies' expertise was obviously far from complete because they were unable to tell a realistic avatar from a human face. By 12 months, they can spot uncanny features, it seems, but not a synthetic face. "This limitation, particularly at the end of the first year of life, is interesting," the researchers said, "because infants of this age have already become sufficiently specialised for human faces that they no longer discriminate the faces of other species and of other races [a process known as perceptual narrowing]".

This study builds on recent research showing evidence of the uncanny valley effect in monkeys. From an evolutionary perspective, the researchers said their results were consistent with the idea that the uncanny valley effect emerges as a result of early developmental experience and was "a useful behavioural adaptation because it enables observers to quickly detect anomalies (e.g. disease) and/or aesthetic value (i.e. beauty) of a face."

Critics of this research may feel that it is rather a leap to assume that the uncanny feeling experienced by adults is felt by babies in any way, just because they look at a face more or less. Moreover, the classic uncanny valley effect is about almost-real robots and faces. This study arguably complicates the issue somewhat by introducing specific abnormal features onto synthetic faces, therefore making them look unreal. Whilst it's been shown that abnormal features, such as enlarged eyes, are perceived as uncanny by adults, this could be a different effect from the discomfort caused by not-quite-perfect hyper-realistic entities.

_________________________________

Lewkowicz, D., and Ghazanfar, A. (2012). The development of the uncanny valley in infants Developmental Psychobiology, 54 (2), 124-132 DOI: 10.1002/dev.20583

Post written by Christian Jarrett for the BPS Research Digest.

- How To Improve Collaboration In Virtual Teams? Members' Avatar Style Could Be Key

When a team rarely gets to be in a room together, it misses out on many of the in-person subtle cues that help members make sense of their relationships. The signals that are available become more important: subtext in email messages, tone of voice on...

- Psychologists Use Baby-cam To Study Infants' Exposure To Faces

An infant sporting the baby-cam, worn upside down to ensure the camera was level with the eyebrows. Image reproduced with permission of N. Sugden.What does the world look like from a baby's perspective? In the first research of its kind, psychologists...

- 31 Terrifying Psychology Links For Halloween!

Spook me, please: What psychology tells us about the appeal of Halloween What do young children know about managing fear? Irrational human decision making during a zombie apocalypse. Extreme fear experienced without the amygdala. How to make a zombie...

- Babies Can Tell The Difference Between Happy And Sad Music

By nine months of age, babies can already tell the difference between jolly jingles and sad ones. You can probably imagine that demonstrating this was no mean feat for researchers, given the obvious difficulties of asking babies what they think. Ross...

- Cognition In Babies

Newsweek's cover story for Aug 15 is all about "Your Baby's Brain". Reads like a literature review lite on cognition in babies -- fascinating, and simple enough for non-scientists to understand. That's the way I like my cognitive science!...

Neuroscience

At what age do babies enter the uncanny valley?

In the 1970s, the roboticist Masahiro Mori noticed a curious phenomenon. As robots became more human-like, their appeal increased but only up to a point. When their human likeness became too realistic (but still not perfect), their appeal plunged. Mori nicknamed this abrupt aversion "the uncanny valley", in reference to the shape of the graph mapping human-likeness and appeal. Are we born with this aversion to the almost-real or does it emerge later?

To find out, David Lewkowicz and Asif Ghazanfar presented nearly a hundred infants (aged between 6 to 12 months) with pairs of faces, to see which they would look at for longer. In the first study, the babies were shown a human face alongside a cartoon face (an "avatar") with enlarged goggle-eyes. The researchers said adults would find the avatar uncanny and would avoid looking at it. The key finding here was that six-month-olds spent more time looking at the uncanny avatar, whereas the twelve-month-olds, like adults, spent more time looking at the human face. Based on this dramatic contrast in preference, Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar said the uncanny valley effect emerges gradually between six and twelve months of age.

These results suggest that none of the babies could distinguish between the realistic avatar and a real human face, and that the older babies in the first study, and all the babies in the second study, must therefore have been using the enlarged eyes to distinguish the goggle-eyed avatar from a human face or realistic avatar face, respectively.

Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar said that the aversion to the goggle-eyed uncanny avatar likely emerged in the older babies as a consequence of their growing expertise with processing human faces, and their association of human faces with positive consequences. However, the older babies' expertise was obviously far from complete because they were unable to tell a realistic avatar from a human face. By 12 months, they can spot uncanny features, it seems, but not a synthetic face. "This limitation, particularly at the end of the first year of life, is interesting," the researchers said, "because infants of this age have already become sufficiently specialised for human faces that they no longer discriminate the faces of other species and of other races [a process known as perceptual narrowing]".

This study builds on recent research showing evidence of the uncanny valley effect in monkeys. From an evolutionary perspective, the researchers said their results were consistent with the idea that the uncanny valley effect emerges as a result of early developmental experience and was "a useful behavioural adaptation because it enables observers to quickly detect anomalies (e.g. disease) and/or aesthetic value (i.e. beauty) of a face."

Critics of this research may feel that it is rather a leap to assume that the uncanny feeling experienced by adults is felt by babies in any way, just because they look at a face more or less. Moreover, the classic uncanny valley effect is about almost-real robots and faces. This study arguably complicates the issue somewhat by introducing specific abnormal features onto synthetic faces, therefore making them look unreal. Whilst it's been shown that abnormal features, such as enlarged eyes, are perceived as uncanny by adults, this could be a different effect from the discomfort caused by not-quite-perfect hyper-realistic entities.

_________________________________

Lewkowicz, D., and Ghazanfar, A. (2012). The development of the uncanny valley in infants Developmental Psychobiology, 54 (2), 124-132 DOI: 10.1002/dev.20583

Post written by Christian Jarrett for the BPS Research Digest.

- How To Improve Collaboration In Virtual Teams? Members' Avatar Style Could Be Key

When a team rarely gets to be in a room together, it misses out on many of the in-person subtle cues that help members make sense of their relationships. The signals that are available become more important: subtext in email messages, tone of voice on...

- Psychologists Use Baby-cam To Study Infants' Exposure To Faces

An infant sporting the baby-cam, worn upside down to ensure the camera was level with the eyebrows. Image reproduced with permission of N. Sugden.What does the world look like from a baby's perspective? In the first research of its kind, psychologists...

- 31 Terrifying Psychology Links For Halloween!

Spook me, please: What psychology tells us about the appeal of Halloween What do young children know about managing fear? Irrational human decision making during a zombie apocalypse. Extreme fear experienced without the amygdala. How to make a zombie...

- Babies Can Tell The Difference Between Happy And Sad Music

By nine months of age, babies can already tell the difference between jolly jingles and sad ones. You can probably imagine that demonstrating this was no mean feat for researchers, given the obvious difficulties of asking babies what they think. Ross...

- Cognition In Babies

Newsweek's cover story for Aug 15 is all about "Your Baby's Brain". Reads like a literature review lite on cognition in babies -- fascinating, and simple enough for non-scientists to understand. That's the way I like my cognitive science!...